Home and a sense of place.

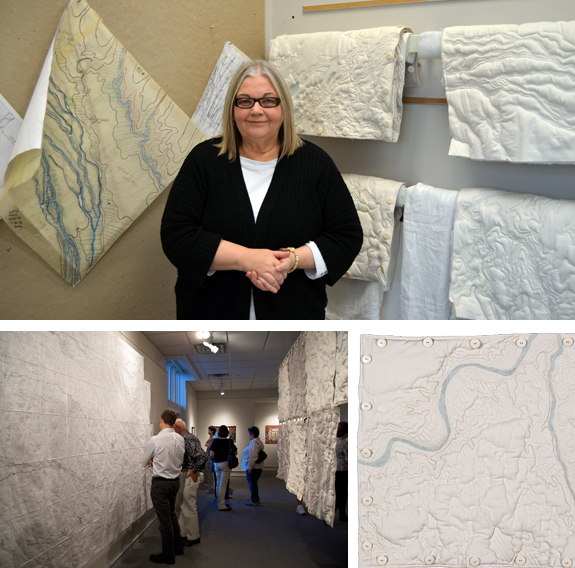

This is what Associate Professor of Art Liz Ingraham set out to discover with her project, “Mapping Nebraska,” a drawn, stitched and digitally imaged cartography and investigation of the state where she lives.

“I always loved topographic maps and those contour lines,” Ingraham said. “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to stitch those contour lines?’ You could quilt it, and it could be a relief form.”

She purchased some National Geographic topographic software for the state of Nebraska. But as she worked in the software, she grew frustrated.

“You start out with something that looks like the state, and then within two clicks, you’re in the middle of this topography,” she said. “And it’s really beautiful, but I wanted to know where I was. I wanted a context. I wanted to know, is this near Scottsbluff or Beatrice? But then when you click out again, you can’t see what you saw before , and you’re completely lost.”

She decided she needed a really big map so she could understand the state as a whole, but couldn’t buy one that was big enough for her needs. So she decided to draw one.

“I wanted a map that showed every town, so I thought, ‘I’ll just draw one,’” Ingraham said.

She divided up the state into 95 33-mile squares, known as her “Liz grid.”

“For a while, about two years, I drew to scale every town, every city, every railroad, every park, every lake, every river and every creek I could see,” Ingraham said. “And the material I was drawing on [Tyvek, a non-woven fabric], you couldn’t erase, so it was both meditative and challenging.”

She then embroidered the section number on each square in braille, and sewed the squares together to make the large map, which she called the Locator Map, which is 15 feet wide by 7 feet tall. One inch equals 2.75 miles on the Locator Map.

As she was drawing the map, though, she came to an important realization.

“While I was doing the drawing, I became very frustrated and a little ashamed,” Ingraham said. “I realized that I didn’t know where I lived. I didn’t feel a sense of connection. I didn’t have a sense of place, and I hated that.”

She also became curious about what she was drawing.

“I’m learning the names of these towns, and I’m seeing these rivers. And what’s up with that section in the west that has what looks like a million lakes in it? What in the world could that look like?”

That led to the next phase of the project when she decided to try to visit each of those 95 sections on the Locator Map to create surveys to document and archive what she has seen and sensed.

“So I started on a series of travels, and I’m about 5,500 miles into it, to date,” she said. “I have about 9-10 sections of the 95 that I haven’t been through at all. There’s a lot to see.”

Along the way, she’s taken thousands of still images and hundreds of hours of video with a dash-mounted FLIP video camera in her car.

“I think the diversity of the landscape surprised me,” Ingraham said. “People told me, but I didn’t understand. People said, “Oh, you should visit the Sandhills,’ and it just kind of went over my head. But I kept looking at that section, because I didn’t like drawing these little lakes. They were very tedious.”

So on one of her trips she went out to that spot on the map—Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge, in the middle of the Sandhills.

“I’ve seen a lot of beautiful places in the world, but that drive. It’s like driving through an ocean of grass, just incredibly beautiful. You go over this gentle rise, and you see this turquoise lake. Then you go over another gentle rise, and you see another lake, and another lake and another lake. That was just unbelievably beautiful.”

Once the Locator Map was complete and as her travels continued, Ingraham began stitching “Terrain Squares,” which are quilted relief forms of the physical topography of selected locations. These were created in a larger scale (1 inch=596 feet).

“At this scale, you can’t see any boundaries, just the terrain, with heights and depths expressed as contour lines and padded relief forms,” Ingraham said.

She hopes to eventually have 95 of these quilted squares. Each one has a fragment of a large-scale, graphic (8’ x 8’) of Nebraska grasses image on the back.

“In theory, you could button these together according to sections according to the map, at some point,” Ingraham said. “Or you could button them together and recreate these 8-foot tall Nebraska grasses.”

A fourth component of the project is the creation of Ground Cloths. These mixed media fabric constructions are a response to a particular location that document what is unseen, remembered or imagined.

“I think of the ground cloths as what you remember, what you imagine or what’s overlooked,” Ingraham said. “It doesn’t have all the rules that these quilted squares have about scale, and it doesn’t have the order the drawn map has.”

The project will be part of the Sheldon Statewide exhibition starting this summer. In the summer, the exhibition will be on display at Sheldon Museum of Art. It will then travel across the state, typically going to eight Nebraska communities for one month at a time. The locations are currently being scheduled and will be available at http://go.unl.edu/statewide.

“Liz’s exploration and mapping of this place displays a process of knowing and transmitting information that ultimately brings us a greater understanding of what it is to live and be in Nebraska,” said Sarah Feit, Assistant Curator of Education at Sheldon Museum of Art.

Tentatively titled “Nebraska,” the Sheldon Statewide exhibition will include Ingraham’s “Mapping Nebraska,” along with other works from the museum’s permanent collection that explore landscapes, people and the things that shape how we understand the state.

“One of the most exciting things to come out of our conversations with her was her willingness to display different portions of her quilted map at each of the Statewide venues,” Feit said. “So when the exhibition is installed in North Platte, for example, visitors will see a portion of her map depicting that area of the state. In this way a portion of Sheldon Statewide will be customized for each of the venues—something we’ve never done before in this way.”

Ingraham is looking forward to getting viewer response from across Nebraska.

“I want to gather what you think about Nebraska. What’s important about where you live? What do you want us to see? Why are you there? Why do you stay?” Ingraham said. “That kind of viewer response is so important to the project.”

Ingraham is also creating a blog at the project’s website, http://www.mappingnebraska.com, where residents can also comment about Nebraska starting on March 1.

“It’s designed around ‘Tell us your story,’” Ingraham said. “You’ll have an opportunity to be part of the project.”

Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts technology assistant Shaina Allison helped to create the website at the end of 2012.

“I loved the idea of bringing Nebraska together,” Allison said. “Her project is incredible. I helped her make the website feel open, like the Plains.”

Abigail Rice, a senior art and art history major from Lincoln, helped work on the project as part of her UCARE (Undergraduate Creative Activities and Research Experience) project in 2010-2011.

“I helped prepare and finish fabric and materials she used in her quilted squares, stitched on buttons, tested materials for stamping, and helped create and install the storage system for her map,” Rice said. “I travelled to a couple of locations outside of Lincoln to photograph the grasses and prairie land and learned to enhance and organize the images. There was a lot of fun experimentation in her studio, and I was thrilled to be a part of it all.”

Ingraham has used four UCARE students on the project, including Rice. In addition to helping her with such a large project, she appreciated the extra set of eyes.

“The UCARE studio assistant gives you another set of eyes and feedback,” Ingraham said. “You need perspective, and this is someone who cares about the work and has a good eye. Who wouldn’t want that?”

Rice said seeing the project gave her a new perspective on her home state.

“Lincoln is my hometown, but I shared Liz’s frustration with knowing so little about the place I lived in,” Rice said. “This project not only helped me gain scope for the size of Nebraska, but I also gained an appreciation for the unique, flat prairie we live on. Nebraska once seemed boring, if you will, and this project made it seem so much more beautiful.”

The project puts a human scale to the map scale.

“Per my own experience, I hope viewers come to gain a sort of intimacy with the landscape and unique sense of place that Nebraska carries,” Rice said. “Mapping Nebraska, through its various visual and tactile elements, quietly invited me to ask how big I was in comparison to a square plot of land and what that meant. I hope others can experience this, too.”

Ingraham said she now feels a better sense of place and connection.

“I do know where I am now. I feel much more grounded,” she said. “My heart has stopped from how much beauty I’ve seen, and I think this project will show some of that. A lot of the beauty in Nebraska, even though there’s a lot of drama, too, but there’s a lot of subtle beauty, and you perceive it across a distance. I think this project shows some of that.”

Ingraham expects to keep on working on Mapping Nebraska for at least another five years until she feels it is complete.

“It’s a big state, so it’s a big project,” she said. “Area and distance and travel are essential characteristics of our state. I think it’s a long trek across the state, and I want a sense of that.

“It’s a long way, and it’s totally worth it.”

• Visit http://www.mappingnebraska.com for more information about the project. Also, if you are interested in learning more about Mapping Nebraska, download her presentation from last fall at the International Quilt Study Center titled “Stitching is Knowing: Mapping Nebraska with Textiles and Thread.” It’s available through the University’s Digital Commons at http://go.unl.edu/dcingraham.