By Tyler Williams, Extension Educator

Farmers use climate and weather information daily and often subconsciously. It is engrained into many farming practices and plays a role in nearly every decision that happens on your operation. When to schedule irrigation, when to start calving, the amount of money you spend on grain drying, the number of gloves you own, etc., are all influenced by our climate and weather.

As we march into the growing season, we can use climatology to plan practices, but, ultimately, there will need to be timely modifications based on the weather.

PLANTING

Planting conditions are heavily dependent on the weather. April 10 or 15 may often be a target for planting corn, since this is past the crop insurance date and the soil temperatures are typically warm enough for corn germination.

The average soil temperature at 4 inches under bare soil on April 15 in West Point, Neb. from 1988–2017 was 50°F, but ranged from 36–61°F. At North Platte, Neb., a similar pattern is evident where the average soil temperature on April 15 (1983–2017) was 49.3°F, but ranged from 39–63°F (data from http://hprcc.unl.edu).

On average (climate), the date looks good, but for any given year (weather), it may not be a wise decision to plant.

The recent 30 year trend for April and May average temperatures is fairly steady; however, March has been increasing by about 1°F per decade in the east and up to 1.6°F per decade in the Panhandle. In 2018, the Panhandle and southwest Nebraska was 1–3°F above normal and north central and southeast Nebraska was just below normal.

Wet fields also limit planting dates. The climate normal (1981–2010) precipitation in Nebraska in April and May is about 4.5 inches in the Panhandle to about 7.5 inches in the southeast. The 30 year trend is for an increase of 0.6 inches per decade in the Panhandle and 0.9 inches per decade in the southeast. Finding that window before the rain hits and the soil temperature is adequate can be challenging. It looks like the corn belt may be on track for another wet spring season.

The data would tell you that planting on a calendar date may not be the best option, but the number of suitable fieldwork days is certainly limited. This year is an example of how “typical” target dates may not work. In a nutshell, don’t waste a good-weather-planting-day.

Visit http://cropwatch.unl.edu for up-to-date information on recommendations for current conditions.

SPRAY APPLICATIONS

Wind speed is a common limitation in the Great Plains for pesticide applications and wind climatology can help estimate potential “windows” for spraying.

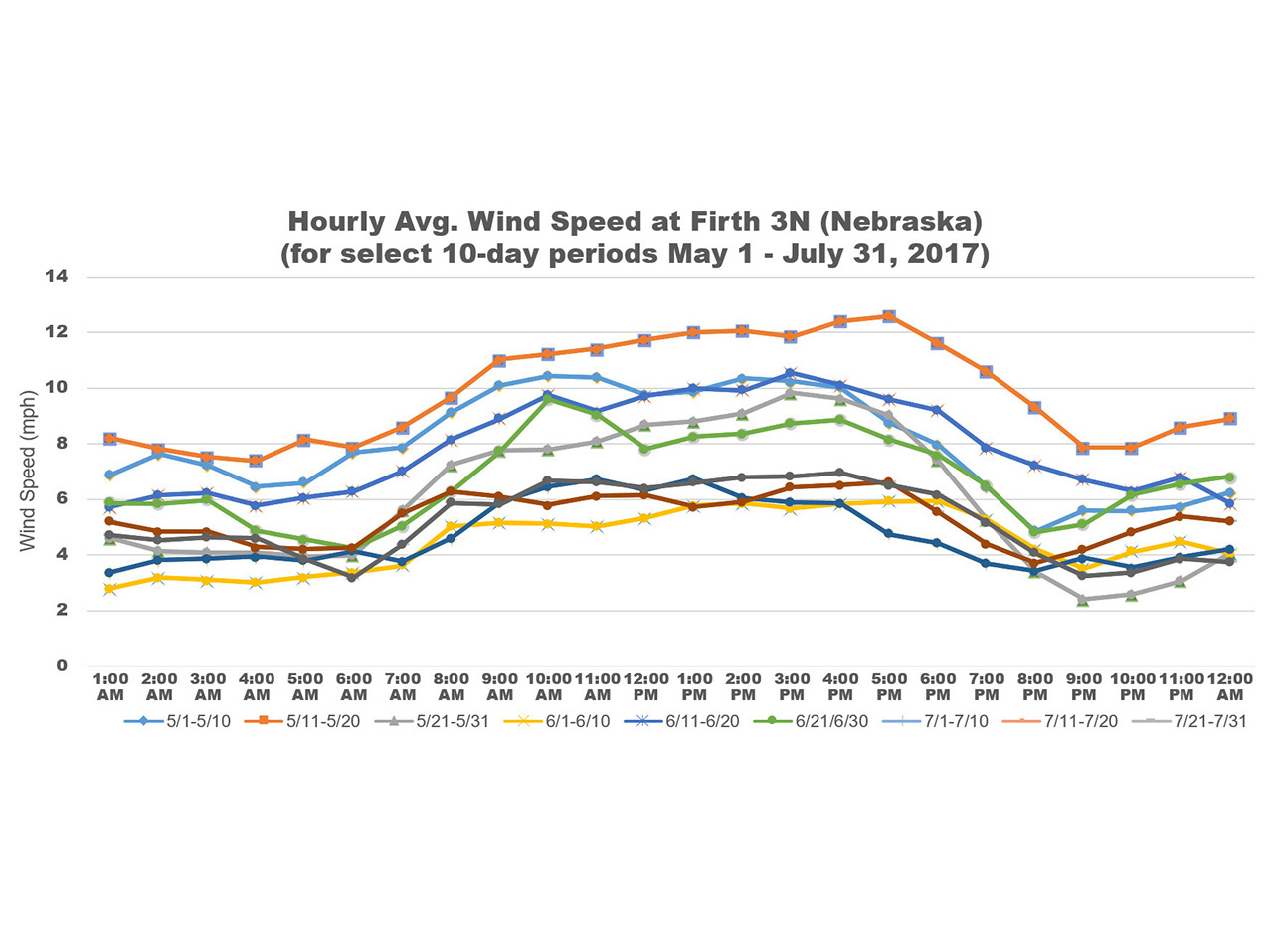

Wind typically begins to pick up speed after sunrise and peaks from 3–5 p.m. (see chart). The average wind speed will also tend to be stronger in May and begin to decrease in late June and into July. These cycles may be useful when determining workload and man-power for applications, but a forecast tool — such as the free AgriTools mobile app developed by Nebraska Extension — will provide hourly weather conditions to more accurately schedule applications.

Climatology can also be used to help understand temperature inversions.

Temperature inversions typically begin to form in the early evening — when incoming solar radiation rapidly decreases — and persist overnight. As the sun rises in the morning and solar radiation increases, the inversion will begin to erode.

Low-wind speeds are a key component for inversions and, as mentioned earlier, the wind speeds decrease overnight and later in the summer. This could increase the risk of an inversion setting in and lasting overnight. Clear skies, low wind speeds and dry air are key ingredients for a temperature inversion.

The weather, in addition to crop and pest growth stage, will determine the actual best date and time of pesticide applications, but climatology may help you think about target windows and potential spray hours available.

CLIMATE OUTLOOK

The outlooks from the Climate Prediction Center for May, June and July are showing increased odds for above normal temperatures for the southwestern half of Nebraska. Most of the U.S. is expected to have better chances for above normal temperatures through the growing season, but portions of the Central Plains, including Nebraska, are a coin flip as usual. (See latest three-month temperature outlook map at http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/lead01/off01_temp.gif)

Our current pattern of below normal temperatures and increased soil moisture (relative to our neighbors) is likely playing a role in our summer temperature forecast. Our cool and wet soils take extra solar radiation to warm, thus reducing the temperature of the air above the surface.

The precipitation forecast is showing increased chances for below normal precipitation from southeastern Texas through Washington and Oregon for May, June and July. As the summer progresses, the target for the increased odds for below normal precipitation is centered over Texas and Oklahoma, as well as the Pacific Northwest. This target was recently over Nebraska, but has since shifted south. (See latest three-month precipitation outlook map at http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/lead01/off01_prcp.gif)

The dry conditions in the Southern Plains and lack of adequate snowpack in the southern Rockies are cause for concern for our summer drought risk. Although our current conditions are favorable, I would use a drought-ready mindset heading into the growing season. It definitely can’t hurt.

Looking to the end of the growing season, we have the potential for an El Niño (warm episode) to form in the Pacific Ocean by late-fall. This gives higher odds for a warmer winter for the northern plains (including Nebraska). The prediction for the spring and summer is for neutral conditions to prevail, which provides very little predictability from ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation). The ENSO cycle is a good long-term forecasting tool when conditions are met.