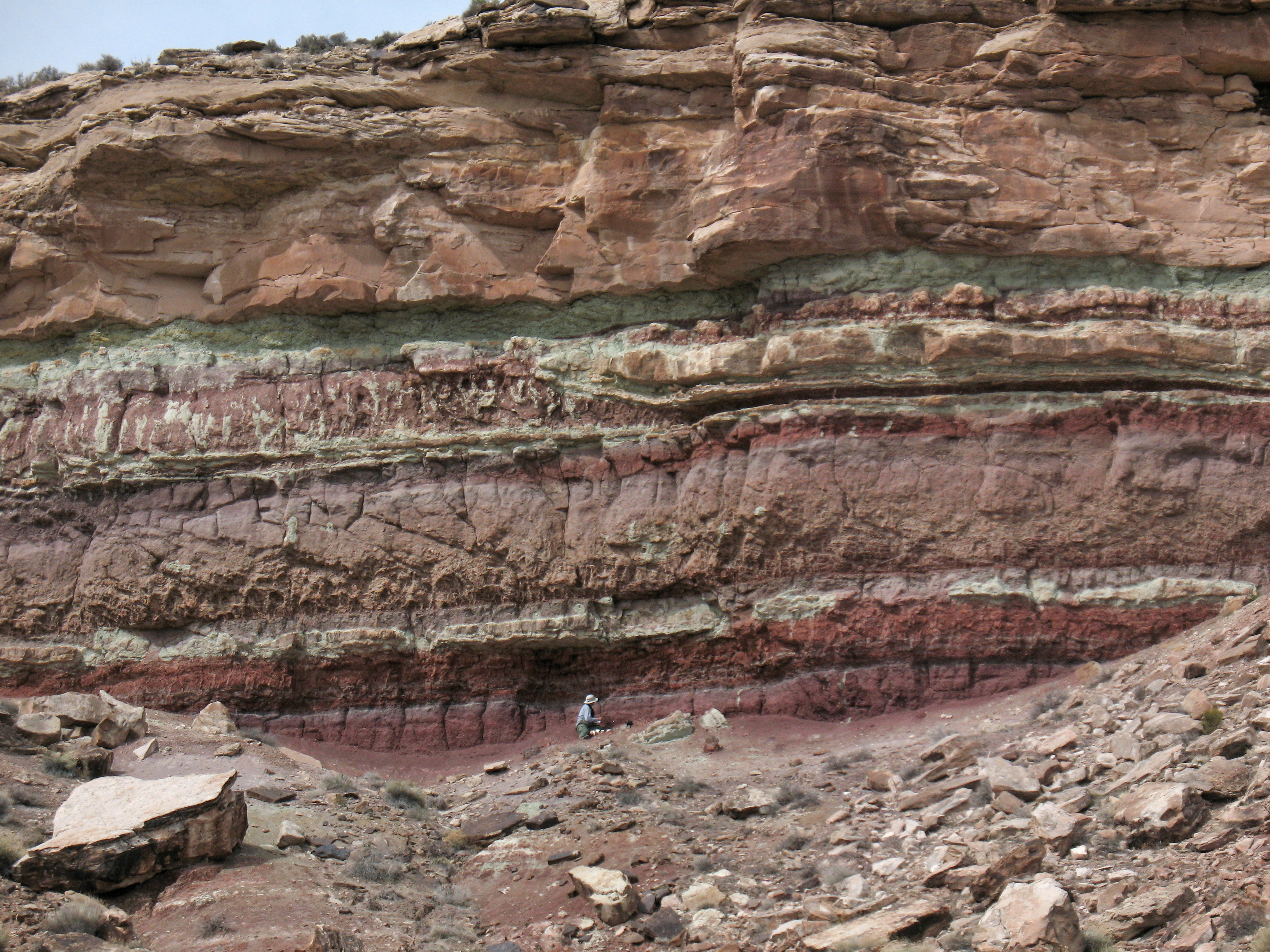

The researchers literally tripped over dinosaur bones to get to their research area, the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, a geologic formation of ancient sediments turned soil and rock that are millions of years old.

Their purpose? To map the ancient soils of the Yellow Cat Member, one of five mappable subdivisions of the larger rock formation in the San Rafael Desert in central Utah, to provide important information as to what ancient environments were like.

The study, led by Matt Joeckel, director of the Conservation and Survey Division at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Natural Resources, showed the Yellow Cat Member’s soils developed in sediments on ancient floodplains after they were deposited and subjected to soil-forming processes over tens of thousands of years or more.

Once formed, the soils were buried again by incremental layers of sediment and the process started all over again.

“We see evidence for at least seven major episodes of floodplain sediment deposition and soil development,” Joeckel said. “The ancient soils that formed are all but identical to the modern soils known as Vertisols, formed where seasonal rainfall occurs.”

The Yellow Cat soils had claylike characteristics where it would swell when wet and contract during periods of dryness. Cracks, some as deep at 1.5 meters, which later filled with other sediments, also were recorded.

“The ancient soils — or paleosols — suggest that rainfall was strongly seasonal, if not monsoonal, and that there were also some very dry periods,” Joeckel said.

“We can learn a lot about ancient climate from the soil,” he added. “We know this area was not forested, but we also know it wasn’t grasslands or prairie. It appeared to be open floodplains, that periodically turned into shallow lakes.”

Though researchers have known for years fossils of dinosaur bones are sandwiched among the sedimentary layers, Joeckel and researcher partners Greg Ludvigson, of the Kansas Geological Survey, and Jim Kirkland, of the Utah Geological Survey, also found features in the sediments that appear to be dinosaur tracks.

“It is no exaggeration that dinosaurs walked on these ancient soils,” Joeckel said.

The trio of research began the Yellow Cat Member study in 2008 as part of a larger effort to study ancient climates and other aspects recorded in the sediments of the Cedar Mountain Formation. By mapping, studying and testing samples from the formations, researchers can learn a lot about the climate of the past.

“Our work on these ancient soils is also determining the numerical age of these sediments so that we can place them within a sequence of global change events of the greenhouse world of the Cretaceous Period,” Ludvigson said. Studies of ancient climates help to improve understanding of future climate change, he added.

To access the study, featured in the November edition of Sedimentary Geology, click here.

Shawna Richter-Ryerson, Natural Resources