CNN picked it up. So did the United Press International news wire service. And US News & World Report.

In the articles, the study on the amount of amphetamines found in waterways in the rural Baltimore, Maryland, area, didn’t seem immediately linked to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, let alone the School of Natural Resources.

But the research was driven by SNR master’s graduate Alexis Paspalof, now Alexis Borbon, during her studies here, and her samples were analyzed by the Nebraska Water Sciences Laboratory at SNR under lab director Dan Snow, Borbon’s advisor.

“This is maybe one of 10 studies ever done on this topic,” Snow said from the lab on Nebraska’s East Campus. “The study’s authors are trying to answer why knowing the levels of amphetamines in waterways is important. People should care because it could be having unintended consequences.”

Borbon initiated the research because of her interest in how amphetamines in waterways may be affecting ecosystems.

“My father is a water treatment operator in California,” she said from her home in Florida. “Growing up, we would spend a lot of time discussing water quality issues and things that potentially could be an issue in the future. At one point, I remember he had come home from a conference where he had listened to a talk about the presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment. I was really intrigued by the implications this meant for water ecosystems.”

When she started her graduate degree under Snow, she knew that’s what she wanted to study.

“When I first began researching this topic, I quickly found there were hundreds of different chemicals that could be measured,” she said. “This is the main reason why there are such few studies. The topic is just a massive undertaking, and it’s difficult to know where to start.”

Borbon decided to start with Adderall, which contains amphetamine. The drug frequently is prescribed for people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, but also is known to be used illegally. Borbon knew research focused on it would be relevant – and likely interesting – to a large segment of the population.

Snow got her in contact with colleague Emma Rosi-Marshall with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies who subsequently introduced her to Sylvia Lee, a post-doctoral researcher who now is working for the Environmental Protection Agency. Together, they and researchers Erinn Richmond with Monash University and John Kelly with Loyola University-Chicago started the project.

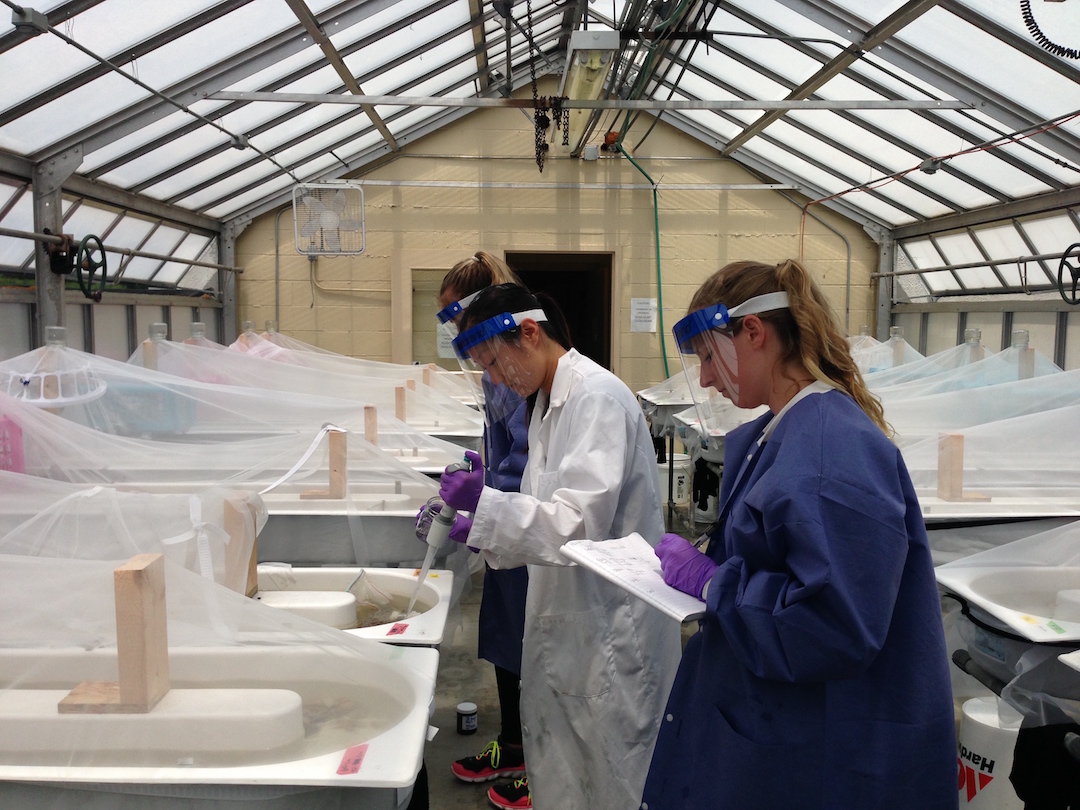

Over a three-week period, the group collected water samples from six streams on the Gwynns Falls and Oregon Ridge watersheds near Baltimore, Maryland. The samples were brought back to the Water Sciences Laboratory to be analyzed using state-of-the-art equipment for measuring low concentrations of pharmaceuticals. The equipment can accurately identify chemical compounds in water and their

concentration down to a few parts per trillion. The Nebraska Water Sciences Laboratory is one of eight or 10 in the country with the capability to test environmental samples at this low concentration.

At the same time, the group created control “streams” where they purposely added amphetamines as a comparison and measured their breakdown, also over a three-week period. (Amphetamines, like other drug compounds, decrease naturally overtime.)

What researchers found was that in both the created streams and the natural ones, the levels of amphetamines were high enough to affect the stream ecosystem. They found growth of bacteria on surfaces was suppressed, bacterial and diatom communities changed, and aquatic insects emerged earlier.

“The results were very surprising,” Borbon said. “The most surprising information was seeing the change in bacterial communities and insect emergence. This was data that was not processed until much later, so when we finally got the data and Dr. Lee put the paper together, it was cool to see what else was really going on.”

Both Snow and Borbon hope the line of research continues with a focus on the potential problems or changes in the environment an increasing presence of pharmaceuticals may cause, but also to determine what is or isn’t a biological effect of the drugs’ presence in waterways.

“It will help put it in perspective,” Snow said. “It would help us answer the: “So, what?” The other researchers agree.

“Ultimately, solutions will lie in innovations in the way we manage waterways,” Rosi-Marshall told the Cary Institute.

Borbon helped collect and process the water samples in 2013 and 2014. She graduated with her master’s degree in natural resources and conservation from Nebraska in 2015. This paper was published in the Aug. 25, 2016, edition of the journal Environmental Science & Technology and immediately started making headlines.

“Having your research be publicized is such an incredible feeling,” Borbon said. “It was very humbling to learn so much knowledge came from what I originally thought would be such an insignificant project.”

-Shawna Richter-Ryerson, Natural Resources

More details at: http://snr.unl.edu