The world of a prehistoric snake — a nightmarish giant, measuring longer than a Tyrannosaurus Rex or a modern school bus — is being brought to life in part by UNL's Jason Head.

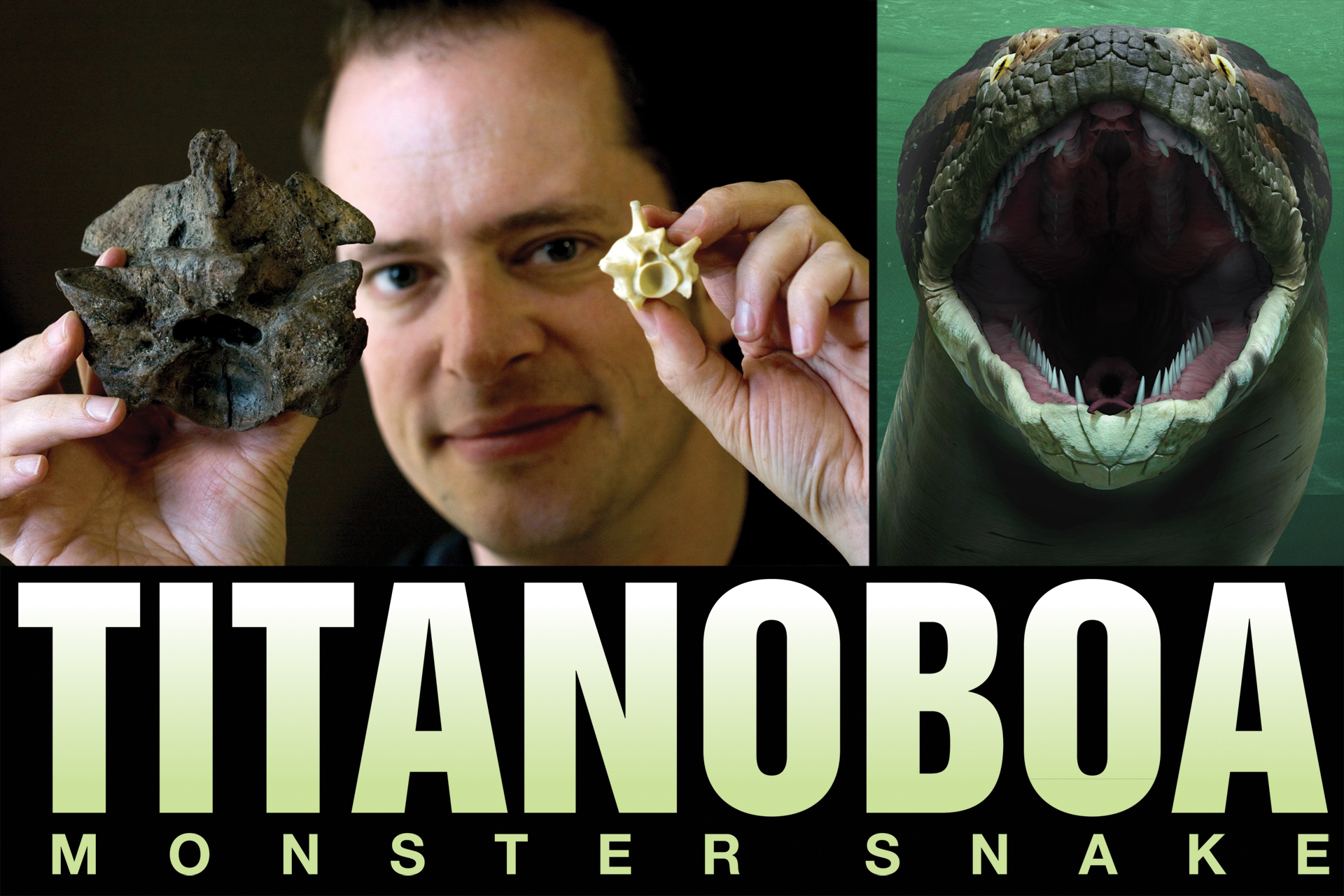

The snake, Titanoboa, and the research team will be featured in a 90-minute, Smithsonian Channel special on the discovery. “Titanoboa: Monster Snake” premiers April 1 at 7 p.m. CDT on the Smithsonian Channel (Time Warner’s HD Channel 95).

Head is an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and curator of Vertebrate Paleontology for the University of Nebraska State Museum.

Watch a video about Head's work on the Titanoboa project at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5twfapSu_N4.

The special is based on the discovery of Titanoboa cerrejonensis, a giant snake that lived nearly 60 million years ago after the age of the dinosaurs. The species was described by Head and a team of scientists from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institution and the University of Florida Museum of Natural History after vertebrae from the massive snake were excavated on a fossil-hunting expedition in Cerrejón, the world’s biggest open-pit coal mine, in La Guajira, Colombia. The snake is estimated to have been 49-feet long and 2,500 pounds.

Head, who came to UNL in 2011, specializes in the evolution of reptiles and their relationship to climate over the past 66 million years. Based on the discovery of Titanoboa, he developed a method to estimate past environmental temperatures from the reptile fossil record. His research was featured in a February 2009 article in the journal Nature.

When he was called on to examine the vertebrae from the colossal snake in 2008, it was clear they had found something special.

“I knew right away that this was a very big deal — that this was going to be something that was going to tell us a lot about the world and that a lot of people were going to be interested in,” said Head. “The important thing about the discovery of the Titanoboa is not just that it is this huge snake. It’s what it tells us about the environment that it lived in.”

The body size of reptiles is dependent on their environment. Unlike mammals, snakes are cold-blooded. The bigger they are the more energy from heat they need to survive. The fossils of ancient snakes essentially serve as paleo-thermometers, giving scientists clues about past environmental temperatures.

Today, the biggest snakes live near the equator and only measure up to about 26 feet in length. The massive size of Titanoboa indicates that the neotropical mean annual temperature during the Paleocene era in which it lived was 30 to 34 degrees Celsius (86 to 93 Fahrenheit), indicating a much hotter climate than previously thought.

Titanoboa lived mostly under water in a large river system, in what is now known to be world’s oldest neotropical rainforest. This ecosystem had diverse flora and wildlife for giant snakes to prey on, such as turtles, crocodilians, birds, and mammals. Titanoboa’s former lush habitat is now a highly industrialized site, rich with coal and fossils buried in layers of the Earth.

Head and his team continue to conduct fieldwork in the active coal mine, where new layers of rock are exposed daily.

“The mysteries we’re still trying to figure out are when this animal first evolved and when it became extinct.”

For the past two years, the Smithsonian Channel has been filming Head and his team as they seek to learn more about Titanoboa and its implications for climate and snake evolution.

In addition to following the team into the Colombian coal mine, amid constant dust and fiery explosions, the film crew documented their fieldwork in Florida, Canada, and Venezuela.

Will we ever see snakes the size of Titanoboa again? Head says the answer is probably no. Today’s environment simply can’t sustain them.

“We are heating up the climate so fast that ecosystems can’t respond in time. They can’t adapt to it. Instead of changing ecosystems, we’re mostly destroying them. It isn’t so much about how warm things get; it’s about how fast things get warm. Instead of having giant snakes what we’ll have in a couple of decades is probably very few snakes of giant size at the equator simply because their habitat will be lost.”

When Head was a child visiting natural history museums, he never expected to be a paleontologist in his position. As an adult, he is proud to be able to provide the research to make other children look around museums like Morrill Hall in awe.

“The greatest thing for me is that if there is a 7- or 8-year-old who is going to watch the special and see Titanoboa, and get inspired to become a paleontologist — then I feel like I’ve made my mark.”

In February 2014, a traveling exhibit explaining the story of Titanoboa will make its way to Morrill Hall in Lincoln, following stops at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and the University of Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville. The exhibit, which features interactive displays and a life-size reconstruction of Titanoboa devouring a crocodile, explores the enormous creature’s discovery, ecology, and evolutionary relationships.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, Smithsonian Institution, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and a number of additional supporters.

— Dana Ludvik, NU State Museum