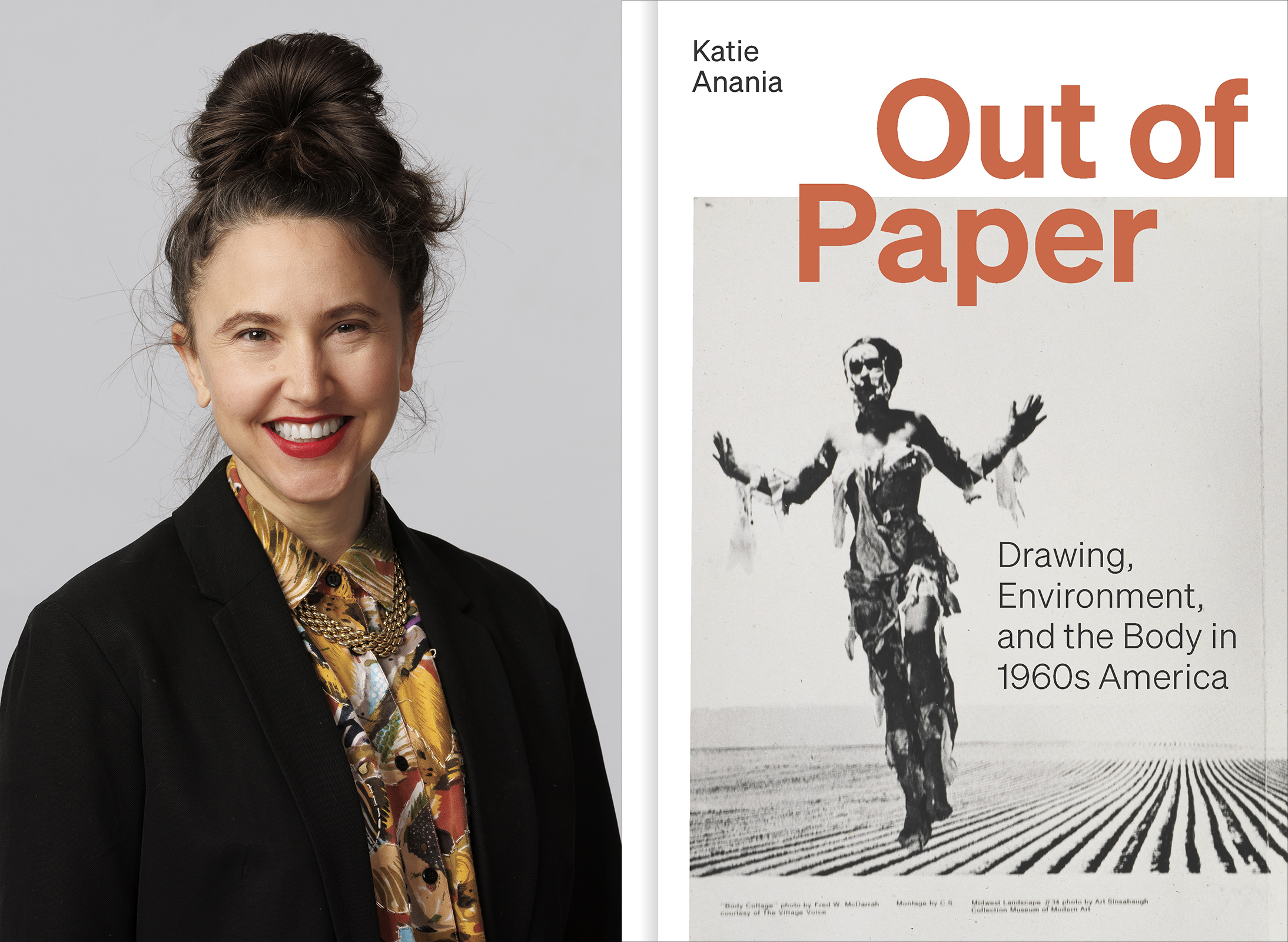

Katie Anania, assistant professor of art history in the School of Art, Art History & Design, has published her first book, “Out of Paper: Drawing, Environment, and the Body in 1960s America.” The book was released Oct. 15 by Yale University Press.

Anania will have a launch event for the book at First Friday, Nov. 1 at Francie and Finch Bookstore, 130 S. 13th St. in Lincoln (time to be announced).

She also held a special launch event in Omaha on Oct. 12 at the Beader-Meinhof Gallery. She will also be giving talks and presentations in October in Los Angeles, Brooklyn and Austin, Texas. And she will have an official reading and book release at the Women’s Studio Workshop in Rosendale, New York, co-sponsored by the Carolee Schneemann Foundation on Oct. 23.

“Out of Paper” is a dynamic look at how U.S. artists used paper to radically redefine the relationship between the body and its surroundings, and to propose new conceptions of ecology in the decades following World War II. In narrating several artists’ drawing projects in Los Angeles, New York, Chicago and Puerto Rico—some public, some private—the book shows how women artists, Black artists, and artists from U.S. colonies used works on paper to imagine new environments and spaces for themselves, using techniques like shredding cutting, erasing, recording and rapid prototyping.

“I’ve always been interested in drawings, first drafts, rehearsals and other remnants of the creative process,” Anania said. “While I was in graduate school and studying contemporary art history, it felt exciting to engage and to research how artists were understanding this part of the process, what they were, what they thought they were making with their drawings, and maybe what they were actually making almost accidentally with their drawings. And it turns out there is a world that can start on a page, and it’s a world that reflects possibility that sometimes isn’t present in a finished work of art.”

The book features artists Carolee Schneemann, William Anastasi, Richard Tuttle, Robert Morris, Rafael Ferrer and Charles White.

“All of the artists featured in the book are connected in some way to the American art world of the 1960s that was growing more global and internationalized, but was also very parochial,” Anania said. “Robert Morris had great success in the New York gallery scene and sold his drawings and sketches for a lot of money, whereas his collaborator Carolee Schneemann had to have a fire sale of her drawings and sketches in her apartment just to pay the bills. Drawings were becoming a currency, but the value of that currency really varied. By studying artists who were connected as part of the same community, but whose fate and critical fortunes varied so widely, I was also able to discover that drawings can tell us a lot about value systems—the way they’re treated, the way they are archived and recovered and preserved.”

Anania said there’s an exciting trend toward looking more closely at drawing in the field of art history.

“I was able to spend time during my postdoctoral research at two different drawing study centers, one of them the Menil Collection in Houston, and one at the Morgan Library in New York,” she said. “There was a lot of discussion in both of those spaces about what it even means to make a whole institution dedicated to drawing in the first place, so we talked a lot about methods, and we tried to even write up some recommendations for how to look at drawings in a way that really differed from looking at paintings and other things. That kind of inquiry was really fed by my research because the 1960s was also this moment where artists were producing drawings and showing them as a work of art most frequently.”

Another layer of her research involved direct conversations with several artists, including Anastasi, Schneemann, Tuttle, Ferrer, Dove Bradshaw, Dorothea Rockburne, Robert Barry and Adrian Piper, among many others.

“And that’s where some of the most valuable discoveries came from,” Anania said. “People just telling me to my face how they felt about drawing, how they used their own drawings, even just how the physical experience of being with paper was central to the overall arc of their projects and careers. You get incorporated into the social life of the art making, and that’s where the real surprises come in.”

The book’s research and writing took more than 10 years. During that time, Anania was a Tyson Scholar in American Art during the spring 2022 semester at the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, where she finished the book and got feedback from her fellow Tyson scholars.

In 2021, Anania became part of a $6 million grant from the National Science Foundation led by UNL aquatic ecologist Jessica Corman on a four-institution team to build a first-of-its-kind database for information on streams, lakes and other inland water systems to study, predict and manage how the ever-changing balance of elements is affecting ecosystems at the regional and national levels.

Under Anania’s leadership, student scientists and student artists collaborated to design better methods for graphic communication to make it more accessible to the public.

“I was special personnel on that grant and was able to expand the art-science component of that grant and invited some postdoctoral scholars in art history and ecology,” she said. “That was invaluable in deciding how I was going to talk about artists talking about science and artists talking about industry and the environmental injury, which is, of course, different from just combing through statistics.”

Anania hopes readers of her book begin to understand how even the most seemingly insignificant creations and materials in our lives are deeply intertwined with industrial processes and social systems.

“Even the things that we make that never go anywhere are a central part or a driving force of our intellectual, physical and material lives,” she said. “The things that we notate to ourselves, like as asides or out of boredom, are structurally so important. And that the same thing that I think these artists were discovering in the moment is that even something like a piece of paper comes from a specific supply chain. It’s connected to an industrial matrix. It’s cut, it’s dyed, it’s bleached usually using the same forces and mechanisms that we’re making bombs for the Vietnam War. It’s inseparable from these operations of industry and the state.”

Anania recently took a field trip with the students in her special topics waste seminar (AHIS 398) to the Lincoln landfill where they learned about what really happens to the trash they throw away.

“In the presentation that our guide gave us, she assured us that nothing disappears. Everything draws from this reserve of resources that are often extracted,” she said.

“Out of Paper” was very labor intensive for Anania as she includes many drawings and illustrations in the book—more than the typical academic book—and had to negotiate image permissions.

“I really wanted the pictures and the reproductions to help tell the story in a significant way,” she said. “I’m hoping that my future projects will, in many ways, be as labor intensive as this one.”

Her next book project is titled “Devour Everything: Art After Agriculture,” which will examine the role of food and nourishment in queer Latinx communities since the United Farm Workers movement.

“It also relies heavily on visual cultural archives to construct the story,” Anania said. “But it’s about queer and feminist artists who collected pieces of visual material for themselves in order to remake agriculture and farming and food sourcing. It’s about this question of whether food can be material like food and soil. There’s this rich history of queer and feminist artists moving onto the land and using ancestral farming techniques. Those are all heavily documented, but rarely talked about. So I’m undertaking this project as a history of reparative practices authored largely by queer, feminist and Latinx artists.”

She hopes to complete it by the summer of 2026.

Anania said all artists can learn something by finding common ground in their processes.

“I’d like to nurture a general interest in getting to know artists and designers and composers and dancers and other creative people and being inquisitive about finding common ground in their processes and your own,” she said. “I think we can all learn from these sorts of casual, but also often very calculated, ways of thinking through material.”