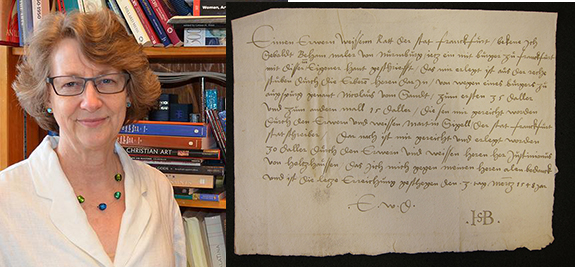

Hixson-Lied Professor of Art History Alison Stewart has discovered two previously unpublished documents from Renaissance painter-printmaker Sebald Beham, during her research in Frankfurt, Germany.

Stewart received a Fulbright Senior Lecturing/Research award to teach and complete research at the University of Trier in Germany in 2014. She received a UNL Layman Award and Hixson-Lied Endowment Research grant for additional research in Frankfurt in 2014 and 2015.

An article on her discovery will be published next year as a chapter in a peer-reviewed book titled “Imagery and Ingenuity in Early Modern Europe: Essays in honor of Jeffrey Chipps Smith,” (Turnhout, forthcoming) honoring Smith, a senior professor from the University of Texas at Austin. She also presented her findings at the Renaissance Society of America Annual Conference in Boston in March.

The two documents are receipts. One shows payments from the Augsburg printer Nicolas vom Sand to Beham from March 3, 1548 for a total of 80 talers, which Stewart estimates that to be around $100,000 in today’s dollars.

The second receipt, written four months later on July 17, 1548, shows another payment from vom Sand for 40 gulden and 15 batzen, which Stewart estimates to be about half the annual stipend of someone well placed or at least $50,000 in today’s dollars.

The receipts do not specify what the payments were for, and Stewart had not known of a connection between vom Sand and Beham previously.

“The research in my field is like a big puzzle, and you put the pieces together,” she said. “Now, I’m starting to find the people that Beham was associated with and who that person lived with part of the time and his publications, so it’s revealing all these layers. This is new information, and you can’t pick up a book on the period and find anything about this printer easily. The receipts give us a lot of information, but they also tell us a lot about what we don’t know.”

The receipts included wording that says in German, “with my own hand.”

“There aren’t many artists who are writing about themselves in this period,” she said. “I don’t have anything else by Beham. I’m coming to the conclusion that unless you were really well known and embedded with the authorities, the information about you doesn’t come down. There has to be a reason your materials were saved.”

Stewart consulted a book written in the 1930s by Walter Zülch on Frankfurt artists. She found the entry on Beham and begin checking the entries with specific documents in the Frankfurt archives.

“When I opened up the folder, I said, ‘Wow! Here they are, and they have never been published,’” she said. “I was very fortunate he had prepared the way for me to do this research.”

Also, Frankfurt was bombed extensively in World War II, so much of the archive burned.

“I am very lucky to have found these documents, and that they survive,” she said.

Beham (1500-1550) was a painter-printmaker who lived in Germany during the first half of the 16th century at the time of the Peasants’ War and Lutheran Reformation. He appears to have been trained by the leading master Albrecht Dürer around 1515-1520.

Beham, along with his brother Barthel and artist Jörg Pencz, were banished from Nuremberg in 1525 as “godless painters,” accused of heresy and blasphemy. They were part of a group of German printmakers known as the “Little Masters,” for their specialization in very small, finely detailed prints.

Beham moved to Frankfurt around 1531. During his two decades in Frankfurt he designed woodcut prints for Nuremberg publishers, book illustrations for Frankfurt book publishers, paintings for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg and, on his own, he made small engravings.

In 2008, Stewart published the book, “Before Bruegel: Sebald Beham and the Origins of Peasant Festival Imagery” (Ashgate, 2008).

The documents she discovered in Frankfurt indicate a wider net of printers with whom Beham worked than was previously known. Her research in Frankfurt will constitute a chapter in a book on Beham she is writing.

“I’m putting together the fact that maybe he was more active than we realized,” Stewart said.

Stewart said she has always been more interested in studying prints, for her art history research.

“I started off in journalism,” she said. “For me, prints tell a larger picture about the way people lived and what they were looking at. Looking at prints tells you more about what a broader range of people were looking at. If you have a print and thousands of these impressions are sent out, you have more people seeing them, so a broader audience.”