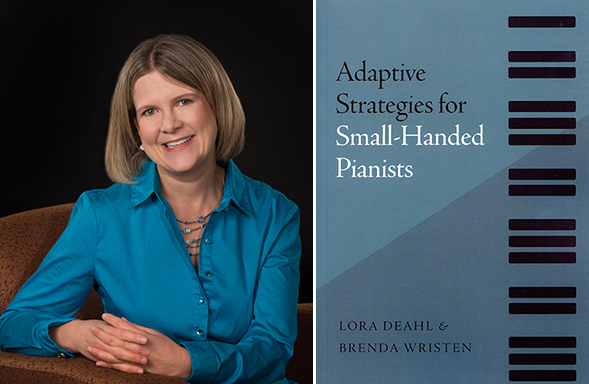

Brenda Wristen has co-authored a book titled “Adaptive Strategies for Small-Handed Pianists,” which has just been released by Oxford University Press. The book brings together information on biomechanics, ergonomics, physics, anatomy, medicine and piano pedagogy to focus on the subject of small-handedness and is the first to focus on the topic.

Wristen is Associate Professor of Piano and Piano Pedagogy in the Glenn Korff School of Music. She co-wrote the book with Lora Deahl, Professor of Piano and Keyboard Literature and Associate Dean of Curricular and Undergraduate Issues at Texas Tech University.

While there is no singular definition for “small-handed pianist,” it is a more prevalent problem than many people realize.

Wristen’s book quotes a 2015 study by Rhonda and Robin Boyle and Erin Booker that looked at the demographics of small-handed pianists.

“Basically, what they found was that among all the pianists they studied, and it was a very large population, 87.1% of the women were small-handed,” Wristen said. “Wow, now that’s a pretty startling statistic. But here’s something that’s even more surprising: 23.8% of the men in their study had small hands as well. And they also observed that highly acclaimed solo pianists tended to have bigger hands. Having a small hand, myself, I’ve certainly been challenged over the years to find ways to play big repertoire.”

Wristen said that small-handedness cannot be determined by just measuring the span between the thumb and fifth finger.

“Small-handedness is not just the span from pinky finger to thumb,” she said. “It can be other things as well, such as the spans between all of the different fingers or the length of the fingers. Sometimes there is a high webbing between the fingers that limits their mobility and flexibility. There are several other factors as well. For this book, we have adopted the functional definition of small handedness, which is if you find yourself struggling with one or more of three areas—fatigue, power and/or covering reach or distance—you are effectively a small-handed pianist.”

Wristen said the book is intended to be a tool to help pianists.

“It’s called ‘Adaptive Strategies for Small-Handed Pianists’ to help people think creatively about their technique instead of doing what most of us tend to do, which is to spend hours of fruitless and potentially injury-causing practice trying to force our hands to be bigger somehow,” she said. “For years, small-handedness has been viewed as a barrier to pianism. Unfortunately in the past, the response to that has typically been to try to stretch the hand, and there have been some devastating injuries that have come about as a result.”

The first part of the book explains the physics and the fundamental principles of movement that inform piano technique. That is followed by applied chapters on particular strategies, including redistributions, refingering, strategies for maximizing reach and power, and musical solutions to technical problems.

Wristen said that maintaining the music that lies behind what’s written on the score remains paramount. It’s just that small-handed pianists need to think about the music in a different way.

“We all have our respect for the musical score, but you can forget that music is not a visual product,” Wristen said. “It’s about the sound that we are producing.”

Wristen calls it the “visual tyranny” of the score.

“There is no reason that we have to use a particular fingering if we can get a better musical result with a fingering that is more suited to our hands,” she said. “With all the strategies that are in this book, I will say that the music comes first. There are more than 300 musical examples contained in this book from the piano literature. In every case, my co-author and I started with ‘How can we respect the musical content of the score and find a way for our bodies to deliver that?’ The main objective of this book is to empower small-handed pianists to look at music and think about music in a way that frees them from that visual tyranny, and that’s a hard skill set to develop.”

Wristen said the issues for small-handed pianists can be traced back to the changes in music of the virtuosic piano literature from the Romantic period (1800s) to the present day.

“Eighteenth century music was written for pianos with a narrower octave on average,” Wristen said.

During the Romantic Period, that shifted.

“We had bigger instruments, we had larger concert halls and we had the age of the virtuosi,” Wristen said. “And that changed things significantly. The average size of the octave on pianos widened during this time, and we went to much thicker textures in piano literature.”

That became a challenge for small-handed pianists.

“When you are a small-handed pianist, I think the instinctive response to technical problems is to think if I just practice longer and I just practice harder, I can make my hand do that,” she said. “Instead, really the question we should be asking is how can I bring about the musical intent and ideation of the score using my unique hand? This book is meant to provide strategies to do that.”

Wristen hopes the book gives small-handed pianists inspiration and permission to adapt.

“Many small-handed pianists just give up playing, and it’s really tragic,” she said. “In addition to being of use to small-handed pianists directly, we hope that this book can help equip piano teachers as they help their small-handed students navigate these waters of challenge.”

Wristen has been studying this issue essentially since she was a master’s student.

“As a master’s student, I had an injury myself from playing the piano, and I first started by looking at injuries,” she said. “What are the injuries that can result from playing the piano? Do we know what causes them? And that sort of thing.”

Later in her doctoral research, where Deahl was her faculty advisor, she did a biomechanical study of different elements of piano technique.

Deahl became interested in her research as well, as they both have small hands and struggled with these issues themselves.

“We have been considering problems of small-handed pianists for a long time,” Wristen said. “This book is the product of more than two decades of our research and our professional experience, and much longer personal experience.”

Wristen hopes the book is a valuable resource for teachers to consider all of the challenges of fundamental pianism.

“Here’s an interesting thing to think about: very large hands,” she said. “It’s a similar problem. It’s just the other end of the spectrum. Having a familiarity with the principles of movement that apply to all bodies and considering how we adapt technique to individual players is information that can benefit all pianists and teachers.”

The musical result continues to be fundamentally at the heart of the book.

“You can’t just say, ‘Well, my hand can’t do that, so I’m going to do this instead.’ You have to start with the musical score. What are the harmonies, and the phrasings and the articulatory and other musical details that need to come out? And then how can I deliver that? We hope that, in and of itself, is an empowering thing,” Wristen said. “It’s not about just realizing the literal markings on the score. It’s deeper than that. It’s looking beyond those written notations to get at the heart of the music, which is a goal for all of music interpretation, regardless of the size of your hand. We start with the musical score, and then we find a way for the hand to produce that musical result that we want.”

Wristen hopes small-handed pianists are challenged to reconsider how they practice.

“If you’re a small-handed pianist stuck in that loop of endless practice— hours and hours and hours spent doing the same thing over and over and over again to no good end, thinking you’re an inferior pianist and potentially risking injury—we want to challenge you to think about your fundamental approach to the instrument,” she said. “We have to practice smarter, not harder.”

For more information on the book, visit https://go.unl.edu/d5fs.