The Husker robotics team took on a problem that wasn’t exactly in their home turf — picking cotton — and came out on top at the 2022 Robotics Student Design Competition.

This event was hosted by the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers and sponsored by Cotton Incorporated. The competition took place at the ASABE Annual International Meeting, which was in Houston this year.

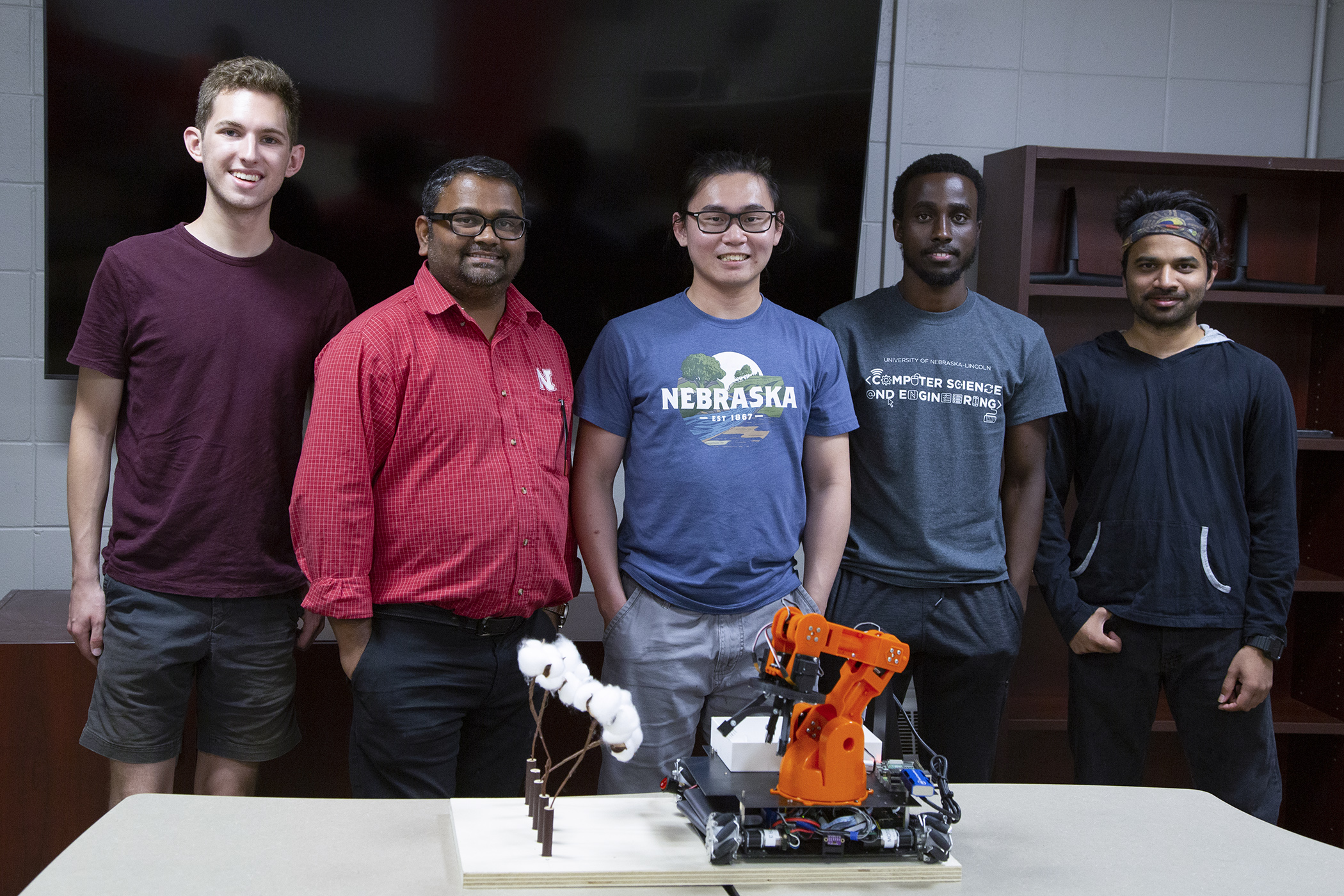

Students on the 2021-22 HuskerBots team were CheeTown Liew, Herve Mwunguzi, Aaron Haake, Krishna Muvva, Salem Nyacyesa Rumuri, Pacifique Mucyo, Theo Joseph and Hessan Sedaghat. The group is advised by Santosh Pitla, a faculty member in the UNL Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources and College of Engineering.

As team members dissected the problem, they realized it could be split into three major parts: detecting, navigating and grabbing the cotton. It would also have to deposit each harvested cotton boll (a term for the clumps that grow on a cotton plant) into a receptacle.

They started working on the project in May, a relatively short timeframe packed with conceptualizing, planning, testing and retesting.

Muvva, who is working on a PhD in computer science and master’s in Biological Systems Engineering, was responsible for detecting the cotton through machine vision and machine learning. One of the challenges of this component was making sure the robot could detect individual cotton from cluster of cotton plants and determine the 3D coordinates of each cotton boll. This would allow it to see how far away each cotton plant was and react accordingly.

Haake, who graduated in May 2022 with a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering, was primarily in charge of designing the robot’s arm. He used a human hand as inspiration, then added extra features to make it even more effective.

“I designed this custom gripper that is capable of gripping with four fingers at the same time to grip the four cotton bolls on the plant,” he said. “We decided to add spikes to get the gripper to sink into the cotton and pull it off. We also wanted the gripper to rotate to match the orientation of the cotton bolls.”

Mwunguzi was responsible for the robot’s “brain,” including its decision-making algorithm and internal communications processes, Pitla said. Mwunguzi got his degree in integrated science from UNL’s College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources and is currently a graduate student in the BSE department.

“The way I look at Herve’s contribution is, the reason this robot is smart is because of the work he did,” he said. “Not only does the mission planning say what it needs to know, but when it sees a cotton boll it comes up with a process for what needs to be done.”

Liew’s job was more behind-the-scenes, but arguably the most important, Pitla said — “the glue that helps keep everyone together.” As competition veteran and the team’s mentor, he assigned roles, kept the project organized and helped with bits and pieces. For example, Liew helped fabricate the chassis, 3D printed the robotics gripper, and developed the depth detection on top of the cotton detection algorithms.

Support members Nyacyesa Rumuri, Mucyo, Joseph and Sedaghat assisted by labeling the images for training machine learning models for cotton detection. Sedaghat also helped Liew with fabrication.

"I played a part in helping with computer vision: recognition and tracking," Mucyo said. "This included image processing, and object focus that would be used by the robot's vision to distinguish cotton from anything else in that area."

The final product contains three microcomputers: Raspberry Pi, Arduino and Jetson Nano. The body of the robot, which sits on top of these devices, is made up of an orange 6-degree-of-freedom robotics arm with four fingers on the end. Beside the robot is a small basket for storing harvested cotton.

The HuskerBots team flew into Houston two days before the competition started on July 18. And that’s when things started to go a bit awry.

Competing in Houston

“When we went (to Houston), everything was working, separately,” Mwunguzi said. “We had to put everything together.”

Once they arrived, they needed to integrate the navigation, computer vision and robotic arm components together, with the pressure of competition day looming close.

“We were up until about 4 a.m. the day before the competition, then woke up 7 or 8 a.m. to go to the competition,” Haake said.

That morning, teammates were nervous and didn’t know how the day would turn out for them. As the group’s advisor, Pitla tried to reassure them.

“Before going to the competition, I was not sure if it was going to work. I said, ‘Let’s not give up, let’s put in the work, luck will favor us,’” Pitla said.

The competition took place in a spacious ballroom at the Marriott Marquis Houston, attracting a crowd of agricultural and biological engineers from all over the world.

Each team’s robot competed by harvesting three rows of cotton, with each row containing 11 plants, on an 8-foot-by-8-foot playing field. Each team had three opportunities to showcase their robot’s abilities, with the best two rounds used to score. Teams won points if their robot picked the cotton without breaking any parts of the plant.

The first round went flawlessly for the HuskerBots. The second round, one of the robot’s fingers broke, although they were still able to complete the task. And in the third round, the Jetson Nano failed and needed to be reset, preventing the bot from finishing that round.

Eight teams participated this year. Once every team had a chance to show its mettle, the HuskerBots’ design came out on top as the only one that had successfully picked cotton without breaking the plant.

One reason for UNL’s victory was because their team members came from a wide variety of disciplines, Pitla said. Because of this, the robot’s system was well integrated, executed machine vision and picked the cotton precisely with a high level of dexterity. Another key difference was in its relatively efficient and precise movements.

The robot attracted a crowd, too, he said. After the competition, many attendees hung around to watch it in action in many fun rounds. “After the third run, people stayed back to see this thing pick. They were very interested. They were thinking beyond the competition.”

Building the next generation

One of the reasons this competition is important is that it offers solutions to real-world issues. For example, the HuskerBots’ design could be installed into larger farm equipment, Pitla said.

“These robotics competitions are inspired by real problems farmers are facing in the field... The inspiration lies there,” he said. “That’s the cool thing about this competition.”

Muvva said he had personal ties to this year’s theme, because up until recently his parents had a cotton farm in India.

“The reason I wanted to be on the team is my parents had a cotton farm in India — it would be fun to work with robots and show them,” he said.

Haake said the practical applications of these challenges is what drew him to this competition.

“It’s a lot more realistic experience in terms of gaining actual practical experience building these systems.”

Mwunguzi agreed, saying this competition helped his longtime interest in robotics take on a new life.

“I was always interested in robotics — and then I found you can do real-world stuff,” he said. “I enjoy when things are not working and then it finally works.”

The HuskerBots have been competing since 2016, and it only had two core members in its first year. Liew, who founded the club in 2017, credits their victory this year with the experience they gained through trial and error.

“The robotics team had a humble beginning, without much knowledge in robotics, we brute forced through the challenges and made many mistakes,” he said. “I think one of the reasons for our achievement came from many years of experience, which we built on the past failures and learned from the other winning teams.”

Haake was the club’s president for the 21-22 year, and this competition is the group’s main event. In the fall, they focus on recruiting and building the essential skills of robot design, such as programming and prototyping.

The group is inclusive to others of all disciplines, including mechanical, electrical, agricultural engineering and computer science, Liew said, since multidisciplinary teamwork is what makes successful designs.

Pitla said clubs like this give students the skills to make a difference in the future of agriculture.

“I think we’re at a very interesting time where we’re thinking about ag and robotics and putting them together,” he said. “We’re creating the next generation of workforce or leaders in IANR, with the goal of food security and energy security and climate smartness.”

***

If you are interested in joining the UNL Robotics Club, please contact cliew2@unl.edu">CheeTown Liew.

More details at: https://bse.unl.edu/news/student-robotics-team-takes-first-international-competition?fbclid=IwAR1iUGt_haA5kF8IUCZsjifqoWPvUe0Iti4AJrRYVWOdwe6LNBjrVp3g888