When University of Nebraska alum Mitch Smith graduated from The College of Journalism and Mass Communications in Dec. of 2011, he didn't imagine he'd be covering a global pandemic so early into his career at The New York Times.

“The last story I did, I traveled to Omaha, where they were treating the cruise ship passengers," Smith said.

That story focused on what it was like to treat the patients and what the road looked like going forward.

"And here we are."

After graduating Smith moved to Chicago to work at the Tribune as a reporter for the metro news desk. Then in 2014, he joined the New York Times Bureau in Chicago and has been there ever since. Smith is one of the reporters responsible for chasing stories across 11 Midwest states. He’s used to traveling several times a month and reporting in real-time. He knew reporting for this project would look a little different with the quarantine in effect—the timing is still real, but with a stationary twist.

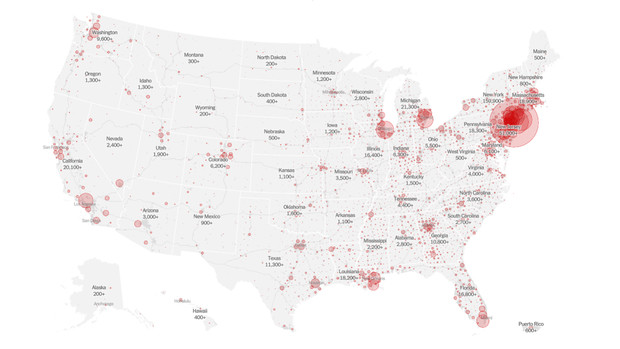

“I’ve been doing this pretty much full time for a month. We started in late January, my editor had this idea to start a spreadsheet that kept track of COVID-19 related deaths,” Smith said. “When the toll began to climb, we realized we needed more help keeping track of the data. We couldn’t keep this going without smart journalists like Libby and Lauryn who provide us with the data we need.”

Junior journalism major Libby Seline and CoJMC adjunct Lauryn Higgins began freelancing and collecting data for The NYT after Smith contacted CoJMC faculty member Joe Starita, searching for student journalists and freelancers he thought would be a good fit for the project.

Seline and Higgins collect every confirmed death related to the coronavirus throughout the country. There are about 20 other NYT reporters, college students and freelancers who are tasked with the same job on the project. During their 8-hour shifts they use government websites, news stations and social media to confirm numbers. Sometimes county numbers and state numbers don’t add up and that requires these data journalists to do some more digging.

During her first week on the job, Higgins learned that the best place to check on numbers is Twitter because health departments often update their numbers on social media before their updating website. The team has also learned that just finding the statewide number is never enough.

The extra steps taken to gather data from sources at a county level are crucial in confirming cases. These steps give county health departments the opportunity to better understand their communities and see how that number compares in others.

The project has given Seline a new appreciation for the data collection process. As an aspiring data journalist, she's taken any and every data journalism class offered at CoJMC and even attended a data journalism conference earlier in the semester.

"In class I'm just handed a stack of 1,000 column data, but now that I’m someone who puts that data together, I know how much work is being put into gathering it,” Seline said. “It's also been fascinating to see what other reporters use this data for.”

In gathering the data, the team has run into its fair share of challenges, but they’re nimble and they do their best to stay ahead. One challenge is that they’re trying to apply consistent rules across an inconsistent field because different health departments report varying amounts of information. Another issue is that as the numbers exponentially grow, states and health departments are changing how they report their data.

“I’m lucky to work at a place with people who are skilled in areas of technology and graphic news because it helps us adjust quickly," Smith said. It’s been this constant state of evolution and with a growing team, but that’s what this situation has called for.”

Smith is always thinking about how the team can use the data collected as a public good. He wants to identify patterns such as which communities have avoided the worst of the virus and which has been hit the hardest. Another main goal is to provide data that informs policy makers and researchers to help them understand what happened, what is happening and what they can do to help make sure this doesn't happen again.

“Journalism is documenting history and we want to do everything we can to provide a record that informs really smart journalism," Smith said.

The team realizes how somber this moment in time is, they’re reporting on fellow Americans who are suffering. It’s something they don’t want to lose sight of, but they also see the importance in never forgetting what happened here.

“I’m excited for the day that we can start reporting on people who have recovered,” Higgins said.