by Geitner Simmons | IANR Media

Urban trees provide numerous benefits to a community. Among those pluses: pollution absorption, stormwater mitigation, atmospheric cooling, habitat enrichment and reduced energy use.

But for a community to get the most out of its trees, careful planning is imperative.

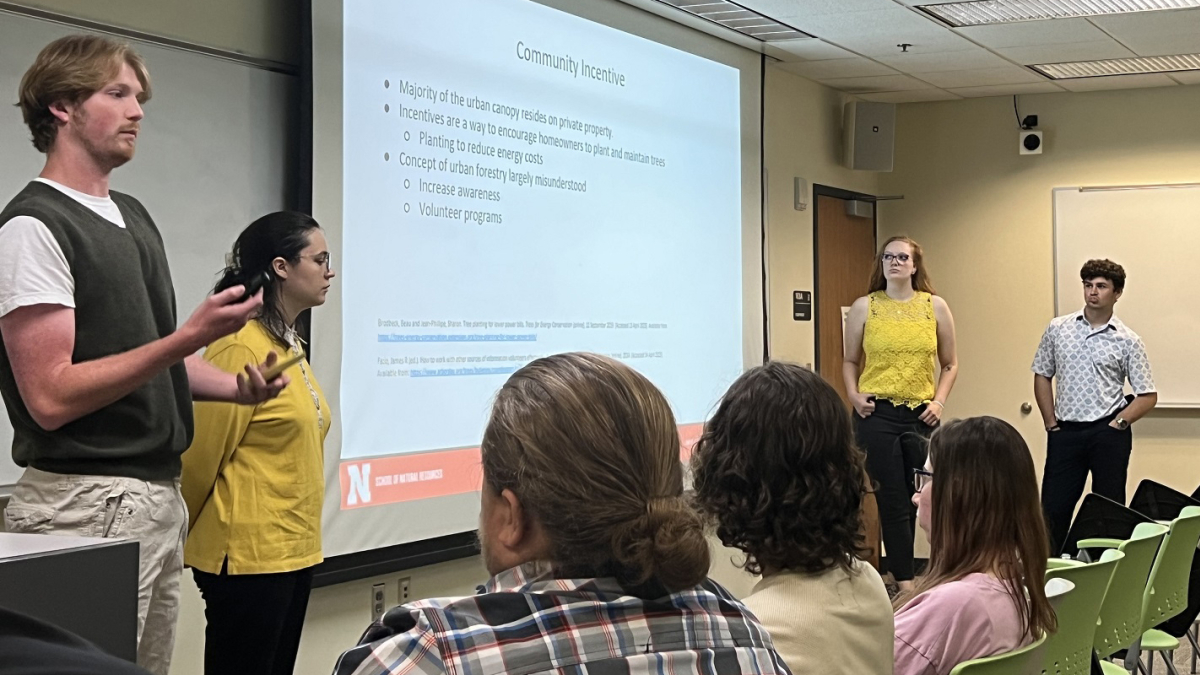

This spring, University of Nebraska–Lincoln students in the Regional and Community Forestry program helped the city of Hickman strengthen its efforts to get the most out of its trees.

Over the course of the semester, students in NRES 457, taught by Lord Ameyaw, assistant professor in the School of Natural Resources, developed an urban forestry management report for Hickman. The community can use that report as a guide to remove, replace and plant new trees going forward.

The collaboration with Hickman was the latest in a series of community-oriented urban forestry projects initiated by the university, beginning with a similar report done for Lincoln in 2020.

The report developed for Hickman has sections on pruning; planting; tree diversity; tree care training; city ordinance review; tree assessment protocol; emerald ash borer planning; and tree equity, a central principle for urban foresters. Community planners should be mindful that trees be distributed across a community’s neighborhoods rather than concentrated in only some of them.

“In the same way we have the same grade of infrastructure of roads, sewers and electricity, we need to be thinking about trees and their benefits as public green infrastructure,” said Graham Herbst, an Omaha-based community forester with the Nebraska Forest Service.

Through analysis of geographic imagery, students found that Hickman is home to 483 trees representing 39 species. Hickman’s southern, long-settled area has considerably more trees than the northern area.

Tree diversity is another guiding principle in urban forestry. In addition to having a range of tree species, diversity goals include factors such as age, genetic composition and tree structure. Diversity in species and genetic makeup strengthen protection against disease and pest infestation.

Students said they benefited from learning how a community’s “gray infrastructure” — sidewalks, buildings, streets — interacts with the local “green infrastructure.”

Hickman has been recognized for prioritizing trees through its participation in the national Tree City USA program, and the new university document is intended to supplement the community’s efforts.

“They can develop a better long-term plan to strengthen their urban forestry abilities, from strategizing to policy,” said Jace Armstrong, who graduated in May with a degree in landscape architecture.

The urban forestry course, like SNR’s forestry program overall, helps students understand that forestry involves a broad range of disciplines, Ameyaw said. Students draw on concepts from community planning, landscape architecture, urban forestry, natural resources studies, horticulture and environmental policy.

“By end of the major here, we’re well rounded in many different subjects, such as plant health, forestry management and wildlife law,” said Zach Zimmerman, a senior majoring in community forestry with an emphasis on urban forestry. “I’ve taken so many courses on each campus at UNL” and talked with specialists from a range of fields. “It’s added to what I can offer to future employers.”

In working directly with communities, students also develop their communications skills, which Zimmerman said was particularly important when it came time to translate scientific or technical details of their work.

The experience “opened my eyes to what actually is involved in being an urban forester in the urban landscape. There’s a lot of hoops to jump through,” Zimmerman said. The experience, he said, “caused me to take a deep dive in some of those policies. It’s also opened my eyes to different programs you can utilize in the future as an urban forester.”

More details at: https://snr.unl.edu/undergrad/majors/reg_comm_forest/