UNL scientists have proven that the makeup of the microbial organisms in the gastrointestinal system is partly a result of genetics - a major breakthrough toward understanding and ultimately figuring out how to manipulate those microbiota to benefit human health.

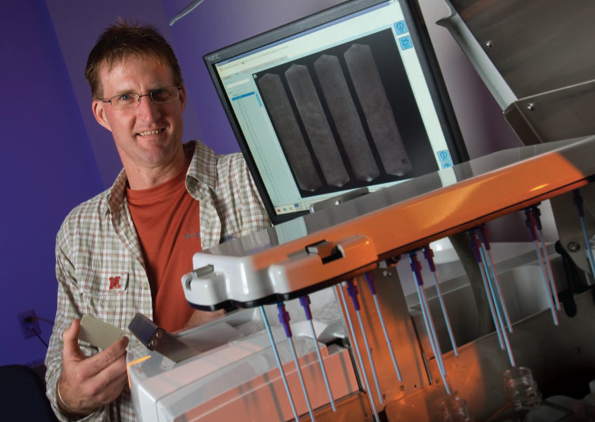

This relationship between gut microbiota and their hosts' genes long has been suspected, but UNL's research is the first to confirm it, said Andrew Benson, UNL food microbiologist who led the research team.

Benson wrote about the findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences with coauthors Daniel Pomp, University of North Carolina; Stephen Kachman, UNL statistics; Etsuko Moriyama, UNL School of Biological Sciences; Jens Walter, UNL food science and technology; and Dan Peterson, UNL food science and technology.

Humans begin life with a sterile gastrointestinal tract, which comprises the small and large intestines. But microorganisms begin to take up residence during birth and rapidly thereafter - initially from the mother, and then from a variety of sources including environment and diet. Ultimately, the makeup of each person's gastrointestinal microorganisms is as unique as fingerprints. It's estimated the GI tract has 10 times more microorganisms than cells in the entire human body.

"It's like the Amazon rain forest in your gut," the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources scientist said.

Gastrointestinal microorganisms have many useful functions: they help with digestion, stimulate cell growth, train the immune system, break down toxins and defend against some diseases. Others, though, are believed to be linked to obesity, coronary disease, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and other diseases.

UNL's Gut Function Initiative is seeking to find ways to encourage the beneficial bacteria and reduce the bad ones.

These latest findings are a key step in that effort, said Benson, who's part of the multidisciplinary GFI team.

It's long been clear the environment affects the makeup of microorganisms in individuals' GI tracts - in addition to what you eat, everything from antibiotics to "how much toothpaste you swallow to how much heavy metal is in your water," Benson said.

It's also been "postulated for some time that the individual host contributes to shaping what in its gut" through its genetic makeup, Benson said. "But it's been very difficult to demonstrate that."

Earlier research focused on human subjects - mostly twins - and had mixed results.

To overcome the variation in human studies, Benson and his collaborator, UNC's Pomp, turned to a mouse model, allowing the scientists to control the environmental factors that affect gut microbiota and hone in on how the animals' genes played a role.

"Using a large population of mice from an intercross of two different breeding lines, we demonstrated clearly that there is host genetic control. We also identified a means by which we can eventually pinpoint the actual genes," Benson said.

So far, the research, funded by the National Institutes of Health, has confirmed that multiple genes in the mouse genome exert the control and these genes control a wide range of gut microorganisms.

"Now we'll use additional mouse models that will allow us to narrow those regions of genes down to individual genes," he said.

As scientists determine how individual genes impact gut microbiota, they hope to develop strategies to help fight diseases that originate in the GI tract. Those strategies might include medicines and food additives.

The research also could have implications for livestock agriculture, Benson said. Many of the microorganisms that cause disease in humans are found in cattle, where they cause no problems. Ultimately, cattle and other food animals could be bred to be less susceptible to carrying these organisms. Benson's team recently established a large-scale project with colleagues at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Meat Animal Research Center at Clay Center to study this issue.

Benson said UNL's expertise in quantitative genomics and statistics and bioinformatics has played a key role in the research.

- Dan Moser, IANR News Service