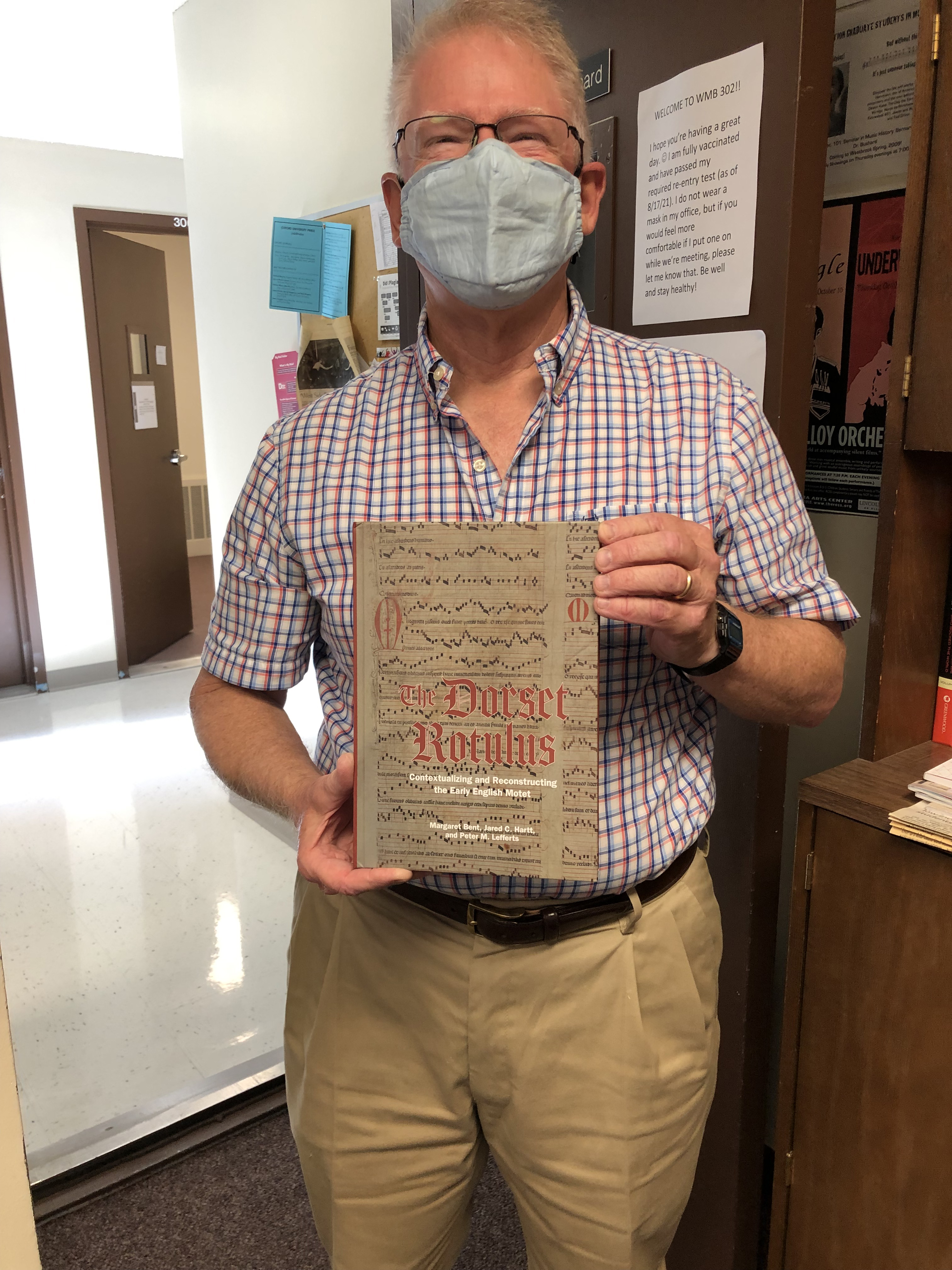

Glenn Korff School of Music Professor of Music History Peter Lefferts’ new book, “The Dorset Rotulus: Contextualizing and Reconstructing the Early English Motet,” was published recently by Boydell Press in London.

The book was researched and written by Lefferts; Margaret Bent, an emeritus fellow of All Souls College in Oxford; and Jared C. Hartt, associate professor of music theory at the Oberlin College Conservatory of Music.

Lefferts received a Hixson-Lied Faculty Research/Creative Activity Grant to support the professional indexing of the book, which was completed between 2017-2021.

A motet is mainly a vocal musical composition from the medieval music to the present. Although the motet in English plays a vital role in the music-historical narrative of the first decades of the 1300s, it has often been overlooked in modern scholarship, due largely to its preservation in numerous, but almost entirely fragmentary sources.

In 2017, substantial new fragments came to light that originated at the Benedictine monastery of Abbotsbury, located above Chesil Beach on Dorset’s Jurassic Coast.

“They turned up in the house of some very rich people in southern England. They’re a very private family,” Lefferts said. “I got to visit there. They have one of these big, English country homes that are very, very old and full of ‘stuff.’ And what happened is that this music probably originated on the southern coast of England at a very large Benedictine Abbey, dedicated to St. Peter, and eventually came into their possession.”

Lefferts said the motets date from around 1300-1320.

“Motets were an important kind of music around the year 1300—let’s say from a range of 1200-1500. They’ve evolved over time,” he said. “But what turned up here were motets that are of English origin. They set sacred Latin words. They’re probably from around 1300, 1310, 1320. We’re pretty confident about that date range. Not much before and not much after.”

Fast forward to the time of the Reformation in the early 1500s.

“If you remember Henry VIII, he got really mad at the Pope and broke off from the Catholic Church,” Lefferts said. “And one of the things he did then was to confiscate all of the monasteries in England and sell them off to rich people in the neighborhood, who were told they had to tear the monasteries down and use the stone to rebuild other things. This was right around 1540. A family acquired this Abbey, knocked it down and took away all of its materials, in particular, all of the documentation that the Abbey had to do with its property, which all became the property of this private family. Over the centuries, those documents from the Abbey, which is about 20 miles away from their house, just got sort of beat up. So in the end, these pieces of music were found in 2016 during a very thorough housecleaning at the bottom of a gigantic wooden chest—like a treasure chest.”

The people who found it contacted their local historical society, and it ultimately came to the attention of Bent.

“She knows very well who I am, and so I was basically the first expert to be brought in,” Lefferts said.

In fact, the music found ties to Lefferts’ doctoral thesis from 1983, which turned into his first book in 1986, titled “The Motet in England in the Fourteenth Century.”

“I did not think I would ever come back to this material. It brought me back into this material that I had been working on at the very beginning of my professional career,” Lefferts said. “But we rapidly realized something of the significance of this. It turns out to be really interesting and important for a lot of reasons.”

Bent and Lefferts brought in Hartt, a music theorist whose professional work studies later Medieval music.

“He had just begun to turn his attention to English motets,” Lefferts said. “So he was brought on to help us reconstruct complete pieces from what are very, very, odd fragments, and he did a great deal of that. Almost like original composition in the style of it to pull these pieces back together.”

The new sources preserve significant portions of four large-scale Latin-texted motets.

“We were able to put together those chunks with what we found and understand better the earlier finds,” Lefferts said. “We were able to suddenly basically have complete pieces. So even though three of the four pieces were known before, they were terribly fragmented. It’s like finding a pot in a field that broke into pieces, and we were able to put all the pieces back together. Jared did a lot of the stitching together of missing music. But there was a fourth piece, which was unique. And we can pretty much reconstruct it in its entirety, and it happens to tell us a great deal about the context for the other three, so that turned out to be remarkably valuable and insightful.”

The parchment leaves were of interest, too, on their own.

“There are two pieces of parchment that we found, and we realized they belong together, one below the other,” Lefferts said. “And there were only two musical staffs missing between them, which meant this music kept going and going without stopping. That’s not how books work, so this music didn’t come out of a book. It had literally come out of a roll or a scroll. And this would have been an imposing scroll that would have had the widest pages of any medieval manuscript of music.”

To build a context for motets on rolls, Lefferts set out to collect all the extant rolls of music from his era from 1250 to 1600.

“The published, scholarly literature that I knew about reported on about six of these, and I was able to find more than 60 by scouring footnotes and indices and lists that somebody did over here or there, but nobody had paid any attention to. I didn’t discover any other rolls, but was able to assemble this huge new list and draft a chapter on these rolls and put it into a more elaborate context.”

While thousands of rolls have survived, Lefferts said very few of them were musical rolls.

“Rolls were used for everyday lists, and my roll was probably very carefully made,” he said. “They knew exactly what they wanted to put on it, and they knew how long it would be. These rolls can go on very long, and you can just keep adding pieces of either paper or parchment. It’s very beautifully made and elaborate.”

Though he plans to retire at the end of the academic year, Lefferts’ next book will examine the sources of 14th century English music of all kinds.

“I am still not done with scholarship,” he said. “That’s what I’ll be doing in retirement. But, you know, it’s fun. It’s interesting. And it’s nice that there are some people who are enthusiastic about it and encouraging me to come back into an area that I had left by the early 1980s.”

Lefferts is professor of music history. He came to UNL in 1989. He has lectured and published extensively in North America and Europe. As an author and editor, his areas of research specialization include medieval and Renaissance English music, the medieval motet, early music notation, early music theory in Latin and English, the tonal behavior of 14th and 15th century songs, and the relationship between church architecture and liturgy. He has also published on topics in American music history. In 2017, he released the book “Manuscripts of English Thirteenth-Century Polyphony (Early English Church Music)” by Stainer & Bell, Ltd.

Lefferts holds the B.A., M.A., M.Phil. and Ph.D. degrees, all from Columbia University. Before coming to UNL, he taught at Columbia University and the University of Chicago.

For more information on Lefferts’ book or to order it, visit the publisher’s site at https://go.unl.edu/4cwj.