By Lyndsey Layton

The Washington Post

The pair of education advocates had a big idea, a new approach to transform every public-school classroom in America. By early 2008, many of the nation’s top politicians and education leaders had lined up in support.

But that wasn’t enough. The duo needed money — tens of millions of dollars, at least — and they needed a champion who could overcome the politics that had thwarted every previous attempt to institute national standards.

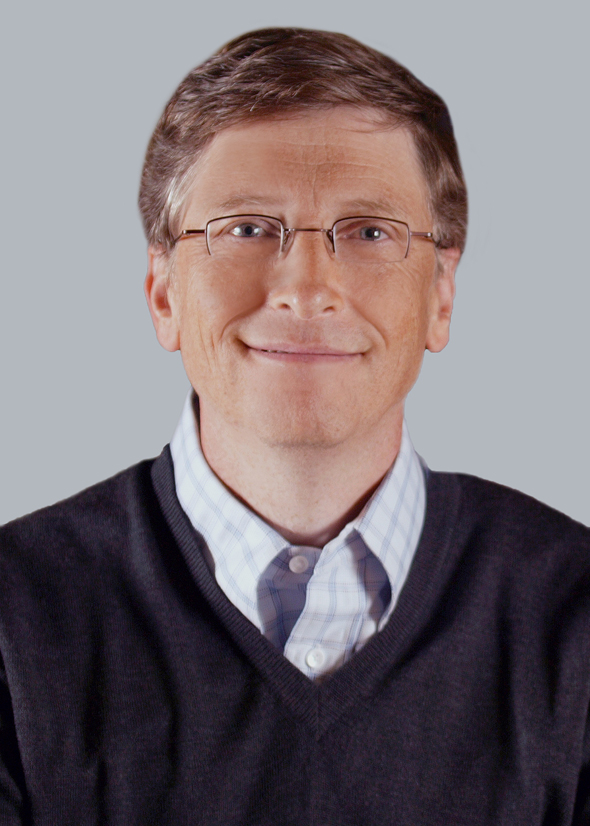

So they turned to the richest man in the world.

On a summer day in 2008, Gene Wilhoit, director of a national group of state school chiefs, and David Coleman, an emerging evangelist for the standards movement, spent hours in Bill Gates’s sleek headquarters near Seattle, trying to persuade him and his wife, Melinda, to turn their idea into reality.

Coleman and Wilhoit told the Gateses that academic standards varied so wildly between states that high school diplomas had lost all meaning, that as many as 40 percent of college freshmen needed remedial classes and that U.S. students were falling behind their foreign competitors.

The pair also argued that a fragmented education system stifled innovation because textbook publishers and software developers were catering to a large number of small markets instead of exploring breakthrough products. That seemed to resonate with the man who led the creation of the world’s dominant computer operating system.

"Can you do this?" Wilhoit recalled being asked. "Is there any proof that states are serious about this, because they haven’t been in the past?"

Wilhoit responded that he and Coleman could make no guarantees but that "we were going to give it the best shot we could."

After the meeting, weeks passed with no word. Then Wilhoit got a call: Gates was in.

What followed was one of the swiftest and most remarkable shifts in education policy in U.S. history.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation didn't just bankroll the development of what became known as the Common Core State Standards. With more than $200 million, the foundation also built political support across the country, persuading state governments to make systemic and costly changes.

Bill Gates was de facto organizer, providing the money and structure for states to work together on common standards in a way that avoided the usual collision between states’ rights and national interests that had undercut every previous effort, dating from the Eisenhower administration.

The Gates Foundation spread money across the political spectrum, to entities including the big teachers unions, the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association, and business organizations such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — groups that have clashed in the past but became vocal backers of the standards.

Money flowed to policy groups on the right and left, funding research by scholars of varying political persuasions who promoted the idea of common standards. Liberals at the Center for American Progress and conservatives affiliated with the American Legislative Exchange Council who routinely disagree on nearly every issue accepted Gates money and found common ground on the Common Core.

One 2009 study, conducted by the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute with a $959,116 Gates grant, described the proposed standards as being "very, very strong" and "clearly superior" to many existing state standards.

Gates money went to state and local groups, as well, to help influence policymakers and civic leaders. And the idea found a major booster in President Obama, whose new administration was populated by former Gates Foundation staffers and associates. The administration designed a special contest using economic stimulus funds to reward states that accepted the standards.

The result was astounding: Within just two years of the 2008 Seattle meeting, 45 states and the District of Columbia had fully adopted the Common Core State Standards.

The math standards require students to learn multiple ways to solve problems and explain how they got their answers, while the English standards emphasize nonfiction and expect students to use evidence to back up oral and written arguments. The standards are not a curriculum but skills that students should acquire at each grade. How they are taught and materials used are decisions left to states and school districts.

Continue Reading:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/how-bill-gates-pulled-off-the-swift-common-core-revolution/2014/06/07/a830e32e-ec34-11e3-9f5c-9075d5508f0a_story.html