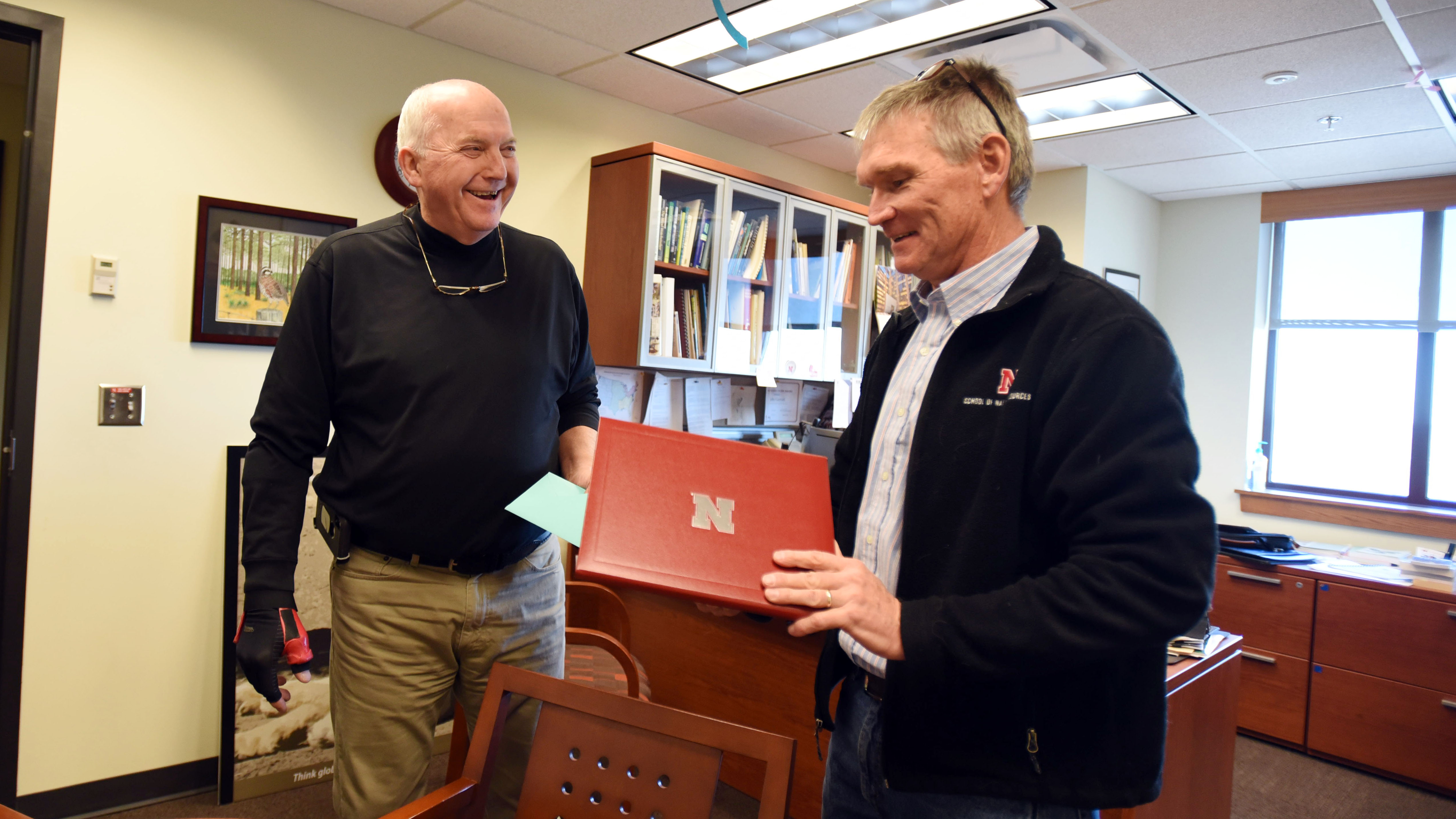

Rick Perk didn’t want a big splash when he decided to retire from the Center for Advanced Land Management and Information Technologies after serving in his role as a geoscientist for 23 years, so on Dec. 18, in a small, private reception, he accepted congratulations and best wishes for the future.

He anticipates little time sitting. Rather he’ll join his wife, Deb, in operating the Eagle’s Nest Bar and Grill part-time at the Hartington Golf Course in northwest Nebraska, and he’ll also help on his brother-in-law’s 4,000-acre farm.

“There’s lots of things I want to do,” Perk said with a smile. “I can’t sit still.”

Perk hasn’t sat still for nearly 55 years, first working as a high school science teacher for 22 years before moving to CALMIT in 1996 for a job in remote sensing.

Over the next 23 years, Perk would help build remote-sensing tools and collect and analyze data for the center. His starting role was to hard-code or program nearly 10,000 pages for the center’s first web server.

“That was before WYSIWYG,” or what you see is what you get, he said, where one could see what the end result would look like as they built pages.

Technology would continue to change over the course of his time with the center at the School of Natural Resources, but Perk was always on top of it, helping to advance the tools CALMIT used, even when that meant building something from scratch on his own.

“My first foray into the field, I walked an individual (remote-sensing) unit in a backpack and carrying a car battery” to keep it charged, he said. “We collected six data points in half a day.”

He came back to the office, walked into the CALMIT director’s office, and said, “I’m going to build you a tractor.”

Goliath was built a short time later from a donated tractor transport trailer and random parts from a nearby scrap pile. Next came Hercules, an even larger more sophisticated remote-sensing data-collection platform. CALMIT soon could collect 1,000 points in half a day.

Perk also was responsible for the airborne research program flights, sitting in the back of a small Piper Saratoga, operating the hyperspectral, thermal and chlorophyll fluorescence imaging systems.

“People think it’s glamourous,” he said, “but it’s the opposite.” Three rear seats have been removed to make way for all the equipment, and Perk — a tall man — would sit crammed between the pilot’s seat and three computer screens, a laptop nearly forced into his lap.

Even so, of all of CALMIT’s programs he’d like to see live on after his retirement, the airborne program is it.

“Fifteen years ago, NASA admin called CALMIT a national resource,” he said. “It could and should be revived, because it has an awesome suite of tools other research institutions don’t have — certainly not in an educational setting.”

“The suite of tools can be applied to myriad subject matter: water, wildlife, migratory species,” he added. “What remote sensing can encompass … .” Essentially, if one can think it, remote sensing likely can play a role.

What it encompassed at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln certainly gave Perk a sense of accomplishment and pride. A sense of purpose, he said about his career.

“But it wasn’t me by myself,” he said. It was a team of people working toward a goal, working to make improvements, working to do good science.

It was a team sad to see him go.

Shawna Richter-Ryerson, Natural Resources