By Ronica Stromberg

Brain scans of B students may offer educators a clue how to improve learning for all students.

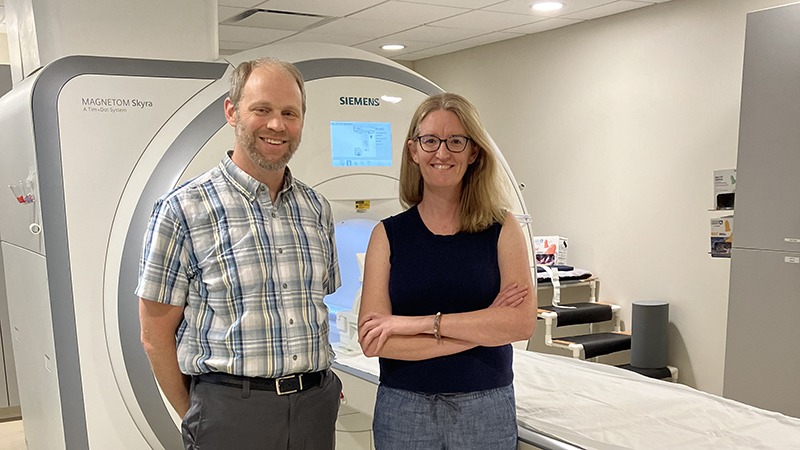

Back in 2020, while looking for ways to improve learning in the sciences, Joe Dauer came up with the idea to scan students’ brains during testing. The life science education researcher in the School of Natural Resources teamed up with Carrie Clark, a neurobiologist, in a grant linking cognitive neuroscience and education.

He said they hoped to detect any variation in brain activity that would explain why some students consistently worked hard yet didn’t earn A’s. If he and Clark could understand that, it should shed light on how teachers could teach better to coax A-level learning from B and C students.

In 2021, the two professors tested 50 university students from an introductory biology class. While individual students lay in an MRI tunnel, the professors projected images of well-known biology models, like of a food web or carbon cycle, above them. The students indicated on a controller whether each of the 36 models had an error or not and how confident they were in their answers. They answered accurately 65 percent of the time.

Using the student test results and the MRI brain scans, Dauer and Clark examined where the students fell on a quadrant of accurate or inaccurate and confident or unconfident. They analyzed the students’ metacognitive sensitivity, the relationship between their accuracy and confidence.

"If you're accurate and you're confident, that's great,” Dauer said of the student test results. " You're aligned. You're calibrated. You know what you know. But if you start to be incorrect or inaccurate but still confident, you're overconfident in what you know, that's not a great thing. You think you know a lot, but you're actually incorrect."

The professors termed students “calibrated” when they were accurate and confident in their answers or when they were inaccurate and unconfident in their answers. The students knew what they knew or didn’t know.

The professors saw a strong relationship between the students being calibrated and their prefrontal cortex of the brain lighting up in the MRI, showing strong activity there. Experts commonly see activity here in scientific reasoning tasks, Dauer said.

Read the rest of the article at https://snr.unl.edu/aboutus/what/newstory.aspx?fid=1149