As winter rapidly approaches, it’s time to look at current conditions and weather patterns expected to impact North America during the next six months.

Although the temperature and precipitation patterns in October 2016 were similar to those in October 2015, the underlying causes were polar opposite patterns in the Equatorial Pacific. Last year, we were entering an exceptionally strong El Nino in October, while this year, a weak to moderate La Nina appears to be unfolding.

We know that weather patterns around the globe are influenced by conditions in the Equatorial Pacific and that these patterns are usually dominant during the North American winter. The impact of stronger events can last into the late spring or span multiple years. Impacts to agricultural production are greatest for the Southern Hemisphere where La Nina and El Nino events impact yields with correlations of 70% or greater.

La Nina conditions are generally a net positive for Southern Hemispheric agricultural production. The general tendency is for Australia to experience above normal wheat yields and for southern Brazil to trend toward above normal soybean yields. South Africa has a positive corn yield correlation, while Argentina corn yields are more drought prone. Under El Nino conditions, polar opposite yield trends are most common for these four countries.

In the U.S., the dominant winter trend during a La Nina event is for wet conditions across the Pacific Northwest southward through northern California, along with the eastern Corn Belt. Drier-than-normal conditions materialize across the southern third of the United States. During El Nino years, these same areas exhibit opposite trends.

Temperature trends during El Nino and La Nina events can be a little tricky because resultant snow cover can have a tremendous impact on temperatures, especially minimum temperatures when deeper snow cover exists. Areas of the country with the highest temperature correlations during El Nino or La Nina events are the northern and southern tier of states.

El Nino events usually result in cool conditions across the southern U.S. as the southern jet stream brings plentiful rain and clouds, while the northern jet remains displaced across southern Canada leading to a split flow pattern that favors above normal temperatures across the northern half of the country. During La Nina events, the southern jet weakens and the northern jet strengthens. We see more cold air intrusions across the northern half of the U.S., while southern states generally lie south of the mean northern jet position and experience warmer-than-normal temperatures due to the lack of active weather associated with the southern jet.

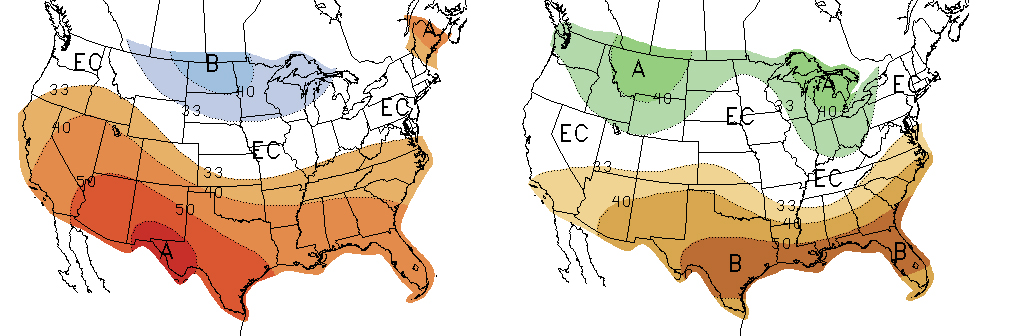

With most models indicating that a weak La Nina event is currently unfolding, expectations are that the northern Plains and upper Great Lakes region will experience below normal temperatures this winter as indicated by the Climate Prediction Center's winter forecast (Figure 1). Their precipitation forecast (Figure 2) hints at above normal moisture across the eastern Corn Belt and Pacific Northwest, while dry conditions are projected for the southern U.S.

It should be noted that the CPC forecasts are based on historical correlations exceeding 70 percent. The eastern Corn Belt precipitation correlations approach 85 percent across portions of Illinois and Indiana.

Even with such high correlations, almost 30 percent of the time, these regions fail to receive the expected conditions. This is why it is critically important to pay attention to how storms are evolving as they move from west to east across the United States during the late fall and early winter.

The La Nina event that is currently unfolding is just beginning to show signs of the typical winter patterns we would expect to see across the U.S. A cursory look at the most recent US Drought Monitor indicates that widespread drought conditions are developing across a substantial portion of the southeastern U.S. Abnormal dry to moderate drought conditions are also developing in pockets from the southern through northern High Plains. Exceptionally wet conditions have been common for the past month across the Pacific Northwest and northern California.

The Gulf of Alaska upper air low has aggressively pushed energy into the Pacific Northwest and is showing no signs of abating. In fact, it appears that it is building further southward as we approach the start of winter.

Storm systems at the surface moving into the western U.S. have churned up a significant amount of surface water and colder than normal sea surface temperatures have developed. There still remains a solid area of above normal temperatures along the southern Alaska coastline that is available to fuel the Gulf of Alaska low, as well as a pocket of above normal temperatures northwest of Hawaii that is feeding energy into the low from its southwest flank.

If the current pattern in the Gulf of Alaska continues to develop, I expect that the upper air low will strengthen and build southward. I also expect the sea surface temperatures to cool along the southern Alaska coastline, which will help play a significant role in the amount of cold air that will be drawn southward into the continental U.S. during this upcoming winter.

Colder-than-normal temperatures are slowly developing across the Pacific Equator. However, the northward extent of this cold pool is being limited by the residual warmth left over from the multiyear El Nino that ended late this spring. There is a substantial pool of cold water below the surface extending from the central through eastern Equatorial Pacific. This alone should support weak La Nina conditions into the early spring.

If the Gulf of Alaska sea surface temperatures continue to cool and expand southward, ocean currents should pull this pool southward along the west coast and eventually into the eastern Equatorial Pacific. If this occurs, this projected La Nina event may strengthen significantly, with an outside chance of becoming a multiyear event. (This is not currently in the consensus forecast of global weather models.)

Active Weather Pattern Possible for Western Corn Belt this Winter

If snow activity is centered over the upper Great Lakes and eastern Corn Belt, Nebraska will likely experience a roller coaster of temperatures this winter, similar to the Polar Vortex winters that have impacted the eastern third of the country in recent years.

So as we approach the beginning of our meteorological winter (December-February), cold air is building across northern Canada and Alaska, but has yet to surge southward into the contiguous United States. Weather models indicate that this may begin to occur as early as next Friday and that a major snowstorm may develop across the northern Plains, possibly impacting the northern half of Nebraska. The amount of cold air pulled southward out of Canada will depend on how rapidly the low moves across the region.

The southeastern U.S. drought also may play an important role in the eventual storm track of winter systems moving across the country. Drought conditions are intensifying as high pressure aloft is forcing lows moving out of the western U.S. to move northeast into the upper High Plains before moving eastward across the Great Lakes and northeastern U.S.

If this pattern persists through the winter, much of the northern High Plains and Great Lakes region are likely to experience heavy snowfall and below normal temperatures. Movement of low-level moisture around the periphery of the southeastern US high pressure would move Gulf of Mexico moisture northeastward from eastern Texas to the southern Minnesota. This opens up the possibility that an active weather pattern may be in store for the western Corn Belt as lows eject eastward out of the western U.S.

Temperatures this winter across Nebraska would be expected to average below normal during a La Nina winter, especially across the northern third of the state. If early season snow activity doesn’t melt across the northern Plains, I would expect below normal temperatures would impact southern Nebraska more than forecasted by CPC in Figure 1.

If snow activity is centered over the upper Great Lakes and eastern Corn Belt, Nebraska will likely experience a roller coaster of temperatures this winter, similar to the Polar Vortex winters that have impacted the eastern third of the country in recent years. Most precipitation activity likely would remain east of Nebraska, but the initial cold air intrusions would spill southward across the western High Plains. High pressure would build in from the west and push the cold air east on a fairly regular basis.

Al Dutcher, for CropWatch

More details at: http://cropwatch.unl.edu/