Wait eight hours; the weather will change.

The common Midwestern saying couldn’t be more accurate than it is for Nebraska where climate variability is the norm, bringing high highs and low lows and wind gusts that can tear off roofs.

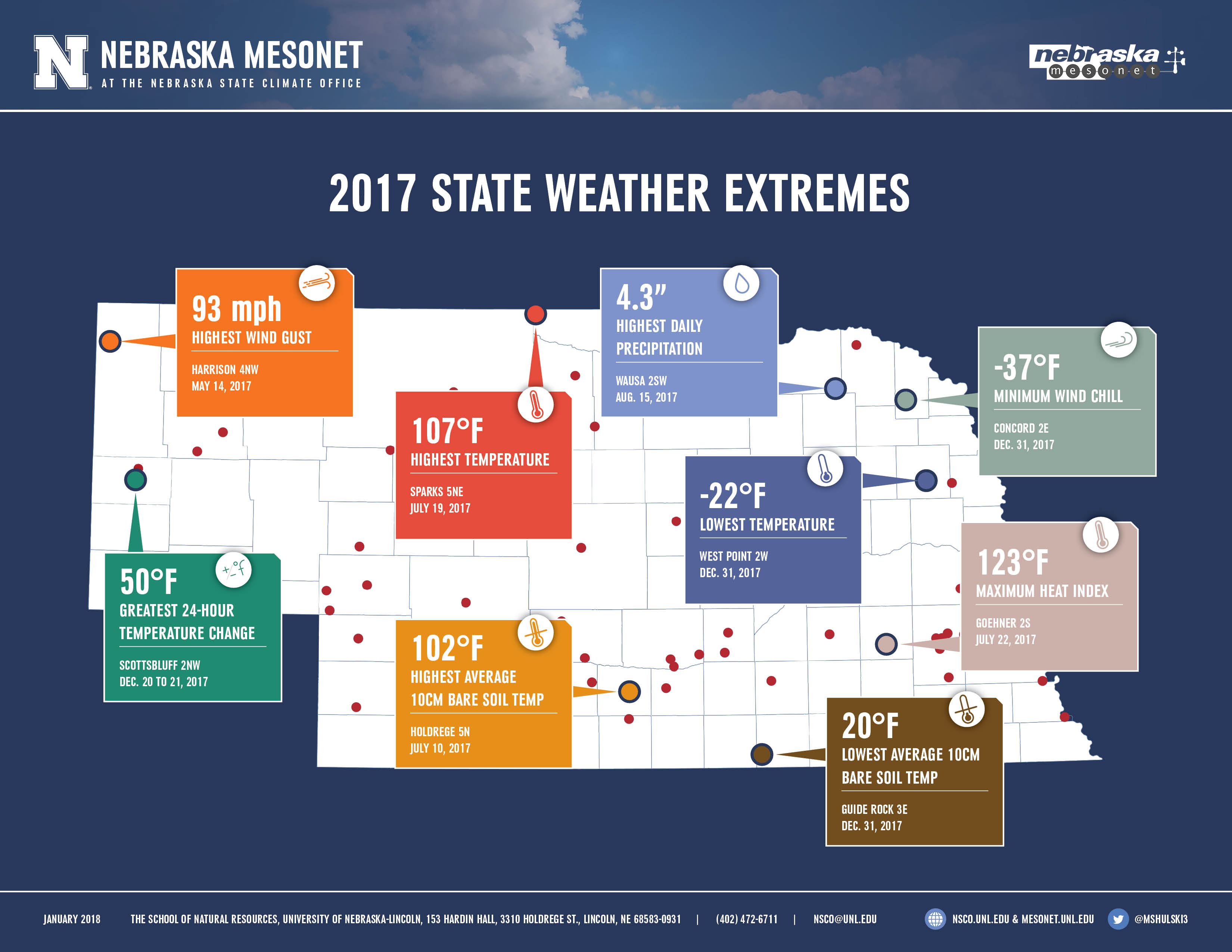

Last year was no different, bringing a 129-degree spread between the highest temperature and the lowest recorded by a Nebraska Mesonet weather station. It also brought a 52-degree 24-hour temperature change, a 4.3-inch rain, and a -37°F wind chill, all recorded by one of the 65 Nebraska weather stations.

While the statistics themselves are impressive, the stories behind 2017’s extreme weather are just as impressive, hammering home just how variable climate is in Nebraska.

January brought warmer-than-normal temperatures, which meant the majority of precipitation that fell was rain, freezing rain or ice instead of snow. Near the middle of the month, an ice storm in southeast Nebraska crippled travel and downed trees and powerlines.

February saw record-breaking high temperatures, including an 83°F day recorded Feb. 22 in Beaver City, followed quickly by a winter storm that dumped 5 inches and then 17.3 inches of snow on Alliance on Feb. 23 and 24. It became the highest one- and two-day snowfall total ever recorded at the northwest Nebraska station.

Neither of those months registered on the Nebraska State Climate Office’s state annual weather extremes list, though. The first event occurred in May, when a storm system brought tornadoes and high winds to much of the state. A weather station in northwestern Nebraska (Harrison 4NW) recorded a 93-mph wind gust May 14, and two days later, wind gusts reported at above 80 mph flipped over an airplane at Eppley Airfield near Omaha and knocked out power to 17,000 residents.

By the time summer arrived, temperatures were soaring across much of the state, hovering above normal during the day and at night. The highest temperature recorded at a Nebraska Mesonet station was 107°F at Sparks 5NE; the maximum heat index was 123°F at Goehner 2S; and the highest 10-centimeter bare soil temperature was 102°F at Holdrege 5N. The soaring temperatures allowed diseases dependent on warmth and humidity to strike crops, and diplopia leaf streak, a corn disease that develops and spreads in warm conditions, was discovered in Nebraska for the first time.

After a dry, but humid, June and July, August rebounded and dropped heavy rain in the middle of the month. The Mesonet station at Wausa 2SW recorded the highest daily precipitation at 4.3 inches on Aug. 15. By the end of the month, parts of central Nebraska had received more than 9 inches of rain, more than one-third of the region’s normal annual precipitation. August also was cooler than normal, with several city centers not breaking the 90°F mark, a rarity for the state.

As fall settled in, fluctuating temperature extremes arrived. Chadron saw temperatures dip to 32°F on Sept. 6, only to hit 100°F four days later. October also brought plenty of precipitation, and Nebraska City 2NW recorded its third wettest October on record; Lincoln its fourth; and Grand Island its fifth.

Four of the nine weather extremes reported for the state, though, fell in December. Temperatures started the month above normal, but turned frigid Dec. 20 and stayed that way through the end of the year. Scottsbluff 2NW recorded the greatest 24-hour temperature change from Dec. 20 to 21, when the thermostat dropped 50 degrees to 2°F. The lowest temperature (-22°F at West Point 2W), the minimum wind chill (-37°F at Concord 2E), and the lowest average 10-centimeter soil temperature (20°F at Guide Rock), were all recorded on Dec. 31 to bring in the new year.

It, too, will be a year variable in nature.

Other reports

NET Nebraska aired a 2017 Weather and Climate in Review, featuring Martha Shulski and Tyler Williams, both of the Nebraska State Climate Office, on Jan. 3. Listen to it here.

Shulski also spoke with Market Journal, providing a recap of temperatures and precipitation the state in 2017. Watch the clip here.

###

The Nebraska Mesonet is part of the Nebraska State Climate Office at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Natural Resources. For more information, visit nsco.unl.edu.

— Shawna Richter-Ryerson, NSCO; Martha Shulksi contributed to this report.

More details at: https://go.unl.edu/d6cs