The National Drought Mitigation Center in January 2019 switched to a streamlined method for reporting local drought conditions, and is working with state agencies and other partners across the country, notably the National Integrated Drought Information System, to promote use of the new form.

“This new form works really well on mobile devices, including photo uploads, which is one of the features that people have been requesting,” said Kelly Helm Smith, NDMC drought impact researcher. “It also builds on the condition-monitoring scale developed by CoCoRaHS, which people also really seem to like.”

Researchers across the country, including the Community Collaborative Rain Hail and Snow Network, the Carolinas Integrated Sciences Assessment, the Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program, and the drought center, are developing tools for “condition monitoring,” focusing on collecting ongoing reports, wet or dry, rather than crisis-driven reports.

“We want people to tell us what they are seeing and experiencing whether it is wet or dry,” Smith said. “That way, we can see the difference between wet, normal, and drought conditions, which actually varies from place to place.”

In addition to working on appealing ways to get people to submit their drought-related observations, researchers are working with decision-makers such as state drought coordinators to learn what type of condition or impact information would be helpful to collect from observers. The launch of the test form in 2018 coincided with emerging drought in Missouri, so Missouri state climatologist Pat Guinan, extension agents, agencies and ag interest groups all publicized it, resulting in a bumper crop of observations from that state.

Looking back on the experience, Guinan said observations such as one from a city official with a photo, saying the town’s reservoir had never before been so low, were particularly helpful. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources also re-posted all of the photos that observers collected to its website.

Since 2005, the center has offered the Drought Impact Reporter, a first-of-its-kind resource that provides a nationwide database of information from a variety of sources, including media and volunteer observers. Those responses are collected and mapped, offering revealing, information-rich updates on how drought is (or isn’t) affecting different regions of the U.S., down to the county. This information sometimes helps U.S. Drought Monitor authors ground-truth physical indicators of drought. The U.S. Drought Monitor is a trigger for federal agricultural relief programs and other decisions.

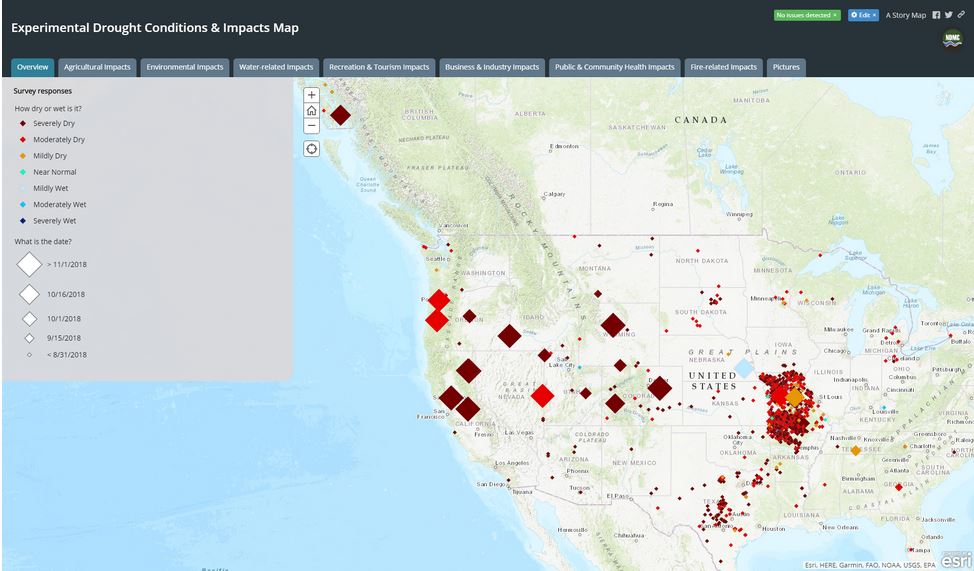

After testing in 2018, the NDMC replaced its old form for collecting observations from people. The new form, which is available at droughtreporter.unl.edu/submitreport, asks users to rank conditions on a seven-point scale, from severely dry to severely wet. Observers can then provide additional information on how conditions affected an array of local concerns, from crop and livestock production to tourism and fire threats.

Under each category, users can select specific events that have been associated with the drought at the time of their report. Did the local golf course require more irrigation than usual? Was a mandatory water conservation policy implemented? Did farmers see a decrease in the weight of their livestock? With a few clicks, observers can contribute to a detailed look at local conditions.

The form lets observers upload a photo that illustrates drought conditions they are seeing, along with caption information that details what the photo shows. Combined, the form, photo and captions will tell the stories of how drought is affecting the country. A pilot test of the new form in 2018 yielded valuable information, such as this submission from a survey respondent in October 2018:

“We are in Owyhee County in Idaho,” the respondent wrote. “No water for crops or cattle, very limited feed and reduced weight on cattle with lower pregnancy rates for cattle. We probably had half of the precipitation of a normal year. Driest year we have had since the drought in the '90s.”

Data from the updated form, created with Survey123 for ArcGIS, is presented on an accompanying map of the U.S., accessible from the DIR Submit a Report page. Users of the 2019 map will be able to filter mapped observations to find specific types of events, such as dry wells or reduced crop yields. Survey responses will show up immediately on the map. Uploaded photos will be processed and viewable on the map in batches and available soon after they are submitted.

Different tabs on the map show how dry or wet observers said it was at each point, the location of observations about impact sectors and specific impacts within those sectors, and the location of observations that include photos. The mapped archive of observations from 2018 is currently accessible via the DIR Submit a Report page and will continue to be accessible via the DIR.

The Drought Impact Reporter was developed with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Risk Management Agency. The new form for collecting observations is supported by NOAA’s Sectoral Applications Research Program and the National Integrated Drought Information System, and in collaboration with NIDIS Drought Early Warning System regions and with USDA Climate Hubs.

###

The National Drought Mitigation Center is one of eight natural resource centers within the School of Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

By Cory Matteson, NDMC Communications Specialist