A University of Nebraska-Lincoln researcher has shown widespread irrigation has resulted in a net moisture loss in Nebraska, a finding that could have worldwide water conservation implications if substantiated by further research.

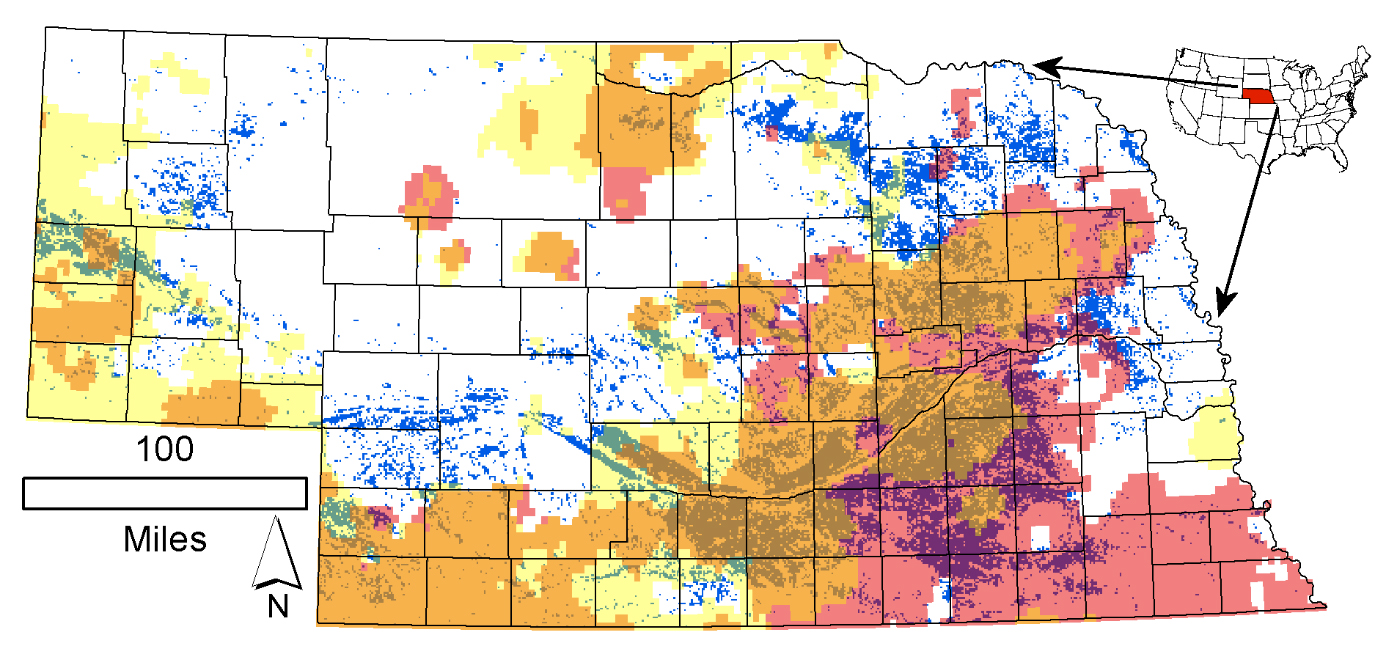

Across Nebraska, the runoff rates have generally dropped by a little more than a tenth of an inch per decade between 1979 and 2015, said Joe Szilagyi, a research hydrologist with the Conservation & Survey Division at the School of Natural Resources. During that same period, statewide precipitation rates have increased by about a tenth of an inch per decade, the opposite of the scientifically accepted relationship between the two variables.

That law, called the Budyko-curve, states that when an area becomes more humid, a higher proportion of precipitation will turn into runoff; when an area becomes drier, a higher proportion of precipitation will return to the air as evapotranspiration.

“Nebraska is in clear defiance of the Budyko-law,” Szilagyi said. “The explanation lies in the about 50 percent increase in irrigated land area over the study period, making Nebraska the leader in irrigated acreage totals within the United States.”

Evapotranspiration rates, fueled by generally increasing air temperatures and expanding irrigation across Nebraska, have grown double the rate of the precipitation increase, leading to dropping runoff rates, Szilagyi said. What is more interesting, however, is that the annual precipitation rates have decreased over the most heavily irrigated regions, while increasing in the other areas of the state.

“The picture is similar when we look at the precipitation rates of the irrigation season only, typically between May and July,” Szilagyi said.

Szilagyi theorizes that the irrigation-enhanced evaporation has a cooling effect over a region, making the overlying air more stable, similar to that of the Great Lakes during the spring and early summer. The air cooled by the evaporating surface becomes denser and less buoyant, forming fewer rain-producing clouds. Once the air leaves the irrigated fields, it becomes more buoyant, eventually dropping its surplus moisture somewhere downwind. That moisture has been reporting falling as far away as Ohio and Indiana, Szilagyi said.

While the wind-driven interstate moisture export from Nebraska has been known for a while, the concurrent local suppression of precipitation over these large-scale and expanding irrigation projects has not been researched much. But, if further research confirms Szilagyi’s finding, it could present a “double-whammy for sustainable large-scale irrigation and water conservation all over the world,” he said.

“Not only does the extra moisture that is released by the irrigated crops leave the area and form a net loss of water, but this loss is made even worse by further reduced local precipitation rates triggered by the large spatial scale over which the irrigation takes place,” he said. And that means the manmade disturbance to the hydrological cycle could have lasting impacts for extensively irrigated areas.

The study was published in the February issue of the Journal of Hydrology.

###

Szilagyi also is a researcher with the Department of Hydraulic and Water Resources Engineering, Budapest University of Technology and Economics.

Shawna Richter-Ryerson, Natural Resources