Steven Barlow, the Corwin Moore Professor in the Department of Special Education and Communication Disorders at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, was selected as the recipient of the biennial Callier Prize in Communication Disorders.

Barlow, who is also the Associate Director of the Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior (CB3), will be honored at the Callier Cares Luncheon April 15. He will present the keynote address at the Callier Prize Conference April 16. Both events will be hosted at the Callier Center for Communication Disorders at The University of Texas at Dallas.

The Callier Prize recognizes individuals from around the world for their leadership in fostering scientific advances and significant developments in the diagnosis and treatment of communication disorders. The award, which alternates between the fields of audiology and speech-language pathology, includes a $10,000 prize.

“I am very honored and grateful,” Barlow said. “It’s an international peer review panel, so that was very nice to be recognized on a worldwide level for our work.”

Throughout his career, Barlow has been dedicated to gaining a better understanding of the role neuroscience plays in babies’ abilities to learn to feed or communicate. He developed the NTrainer System, a therapy device that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2008, which generates pulsed tactile stimulation to the infant’s lips and tongue during tube (gavage) feedings in extremely premature infants.

He’s currently in year three as the principal investigator on a five-year, multi-site randomized-control trial funded by a $2.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health. Barlow and his co-PI, Jill Maron of Tufts University Medical Center, are leading a group of nearly 20 researchers who are aiming to collect data from 155 infants at the CHI Health St. Elizabeth in Lincoln, Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, California, and the Children’s Hospital Orange County in Orange, California. The group is exploring the effects of therapeutic somatosensory stimulation using the NTrainer in extremely premature infants (born less than 29 weeks gestation) on gene expression related to brain development and the attainment of oral feeding skills.

“One major goal is to examine how pulsed somatosensory stimulation modulates the expression of genes that are known to produce proteins that help build pathways in the brain specifically for hunger, feeding, satiation and orofacial function,” Barlow explained. “This is the first large-scale randomized trial in the U.S. that involves this type of experimental approach with extremely premature babies.”

Barlow’s research is not limited, however, to only helping people at the beginning of their lives. He has a newer line of research focused on using a new form of somatosensory stimulation to promote collateral blood flow and preserve brain function in survivors of ischemic strokes, which account for about 87 percent of all strokes.

“We’ve had an interest in stroke for some time because there are many neurobiological principles that we’ve been exploring with the infants that can be applied to the adult model with brain injury,” Barlow said. “One population that will show great promise for plasticity and recovery function are adults that present to the hospital emergency room with large-vessel middle cerebral artery (MCA) ischemic strokes, which result from a clot or blockage of the main artery which supplies vital nutrients and oxygen to key areas of the affected cerebral hemisphere that controls speech, language, limb movements and somatic sensation.”

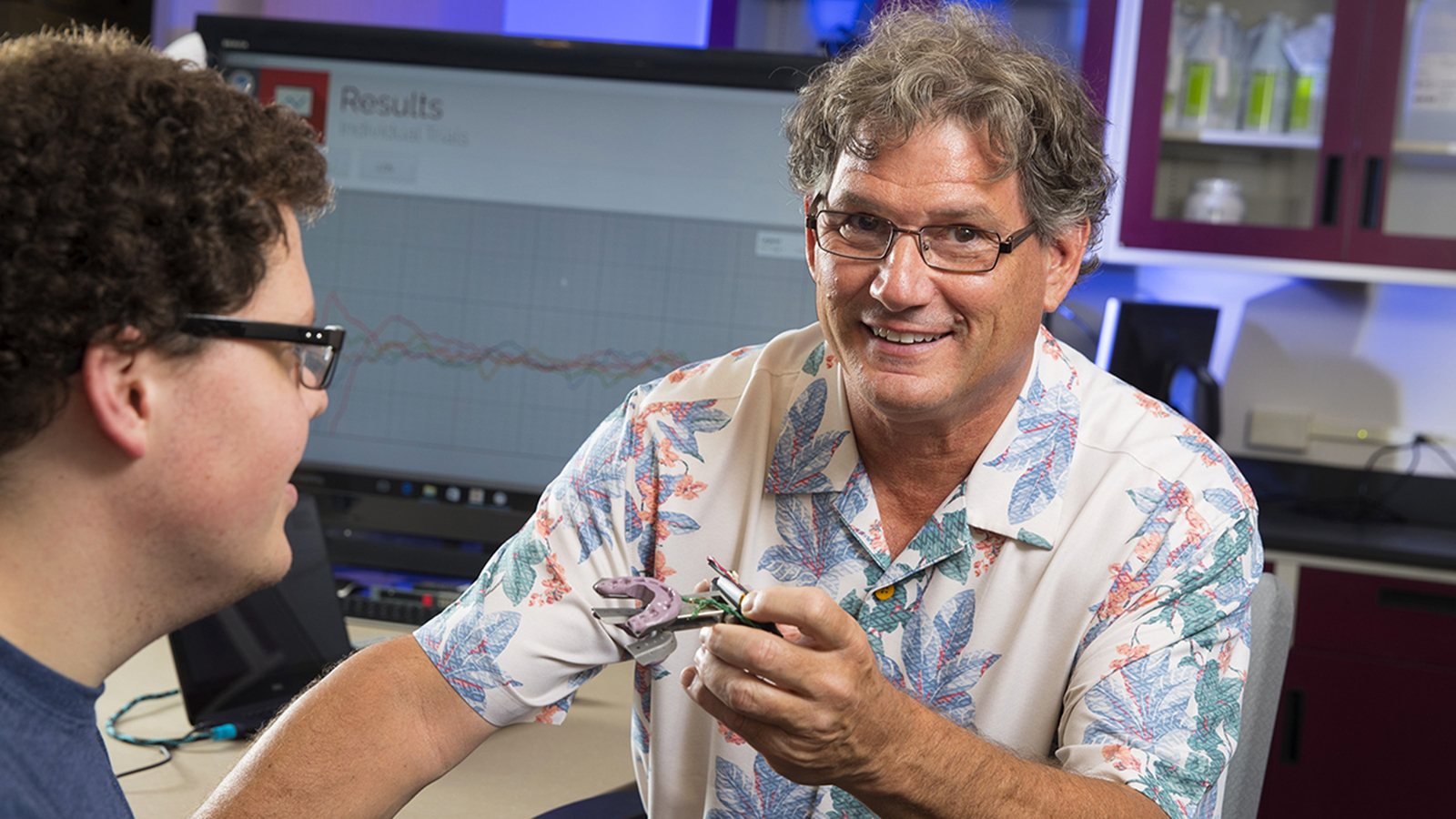

Barlow began collaborating with Greg Bashford, a professor of biological systems engineering and a faculty affiliate at CB3 who specializes in functional transcranial Doppler (fTCD) imaging of the large blood vessels in the brain. They combined Barlow’s innovations in somatosensory stimulation with Bashford’s fTCD technology and ran a series of experiments over the past few years. Last year, Barlow and Bashford, along with graduate students Ben Hage and Jake Greenwood, published findings in the Journal of Neuroimaging demonstrating that the combination of their respective technologies revealed a new approach to non-invasively increase the amount of collateral blood flow in the human brain, which is a central tenet to acute stroke intervention.

Barlow and Bashford are now preparing for a partnership with CHI Immanuel Medical Center in Omaha that will allow them to utilize their technology with stroke patients in the emergency department. They have begun the process by training nursing staff to administer the stimulation under their guidance. Ultimately, Barlow hopes their stimulation system will be available to first responders to initiate treatment within minutes of an ischemic stroke event.

“We’re really excited about it. It’s a very speculative type of research, where the risk-benefit ratio is pretty high, so not a lot of risk, but the potential for benefit can be enormous. This is definitely not a study line where the intervention is for a particular speech problem. Rather, we’re aiming to prevent the devastating sequelae of brain stroke on movement and sensory systems altogether. In that respect, it will have potentially enormous impact across many fields.”

The abbreviated version of Barlow’s curriculum vita features more than 31 pages of accomplishments, including 13 inventions and patents, 250 presented papers, 140 publications, one book, and numerous funded research projects and activities as both an instructor and a researcher. Yet Barlow says the 36 graduate students he has mentored and the many more who have spent time working in his lab are what make him most proud.

“Students – that would be what I’m most proud of. The students that I’ve mentored and the students that I’ve been able to recruit, not only from speech and hearing but from many other fields and bring them into the mix of studying communication disorders. We do it on purpose – we want students in this laboratory from many different backgrounds because of the reciprocal exchange of information and knowledge from one to another. Our speech-language pathology students here at the University of Nebraska are routinely exposed to advanced methods from computer science, electrical engineering, biological systems engineering, medicine, neonatology and neurology. I think those are experiences that are pretty rare, and this is what opens up the view for significant paradigm shift in theory and practice.”