Groundwater levels across much of Nebraska continue to rebound from the historic 2012 drought, according to the 2019 Groundwater-Level Monitoring Report. However, the groundwater-level rises resulting from the historic flooding of 2019 across Nebraska have not yet been completely accounted for. While the flooding had a grave impact on surface water levels throughout much of Nebraska, how it affects the groundwater supply will be measured in the coming years, said University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Natural Resources Geologist Aaron Young.

The reasons for that, Young said, are threefold. Groundwater levels for the annual report are collected each spring, so data from some of the 5,000-plus wells that are measured throughout the state were collected prior to the mid-March floods. Also, Young said, the floodwaters take time to seep into the state’s vast groundwater supply. And in other cases, he said, wells that would typically be examined for the annual report could not be accessed, as they were completely submerged.

“I personally measure about 125 wells out of about 5,000,” Young said. “Last year, there were six that I attempted to measure where, as you were driving up to it, you could look down the road and it was just water. You couldn't even see the wells sticking out of the ground. The flooded areas may have been underrepresented in this year's report. This year, several hundred wells that we normally measure, particularly in Kearney County, around Fremont and some other hard-hit areas, didn't get measured.”

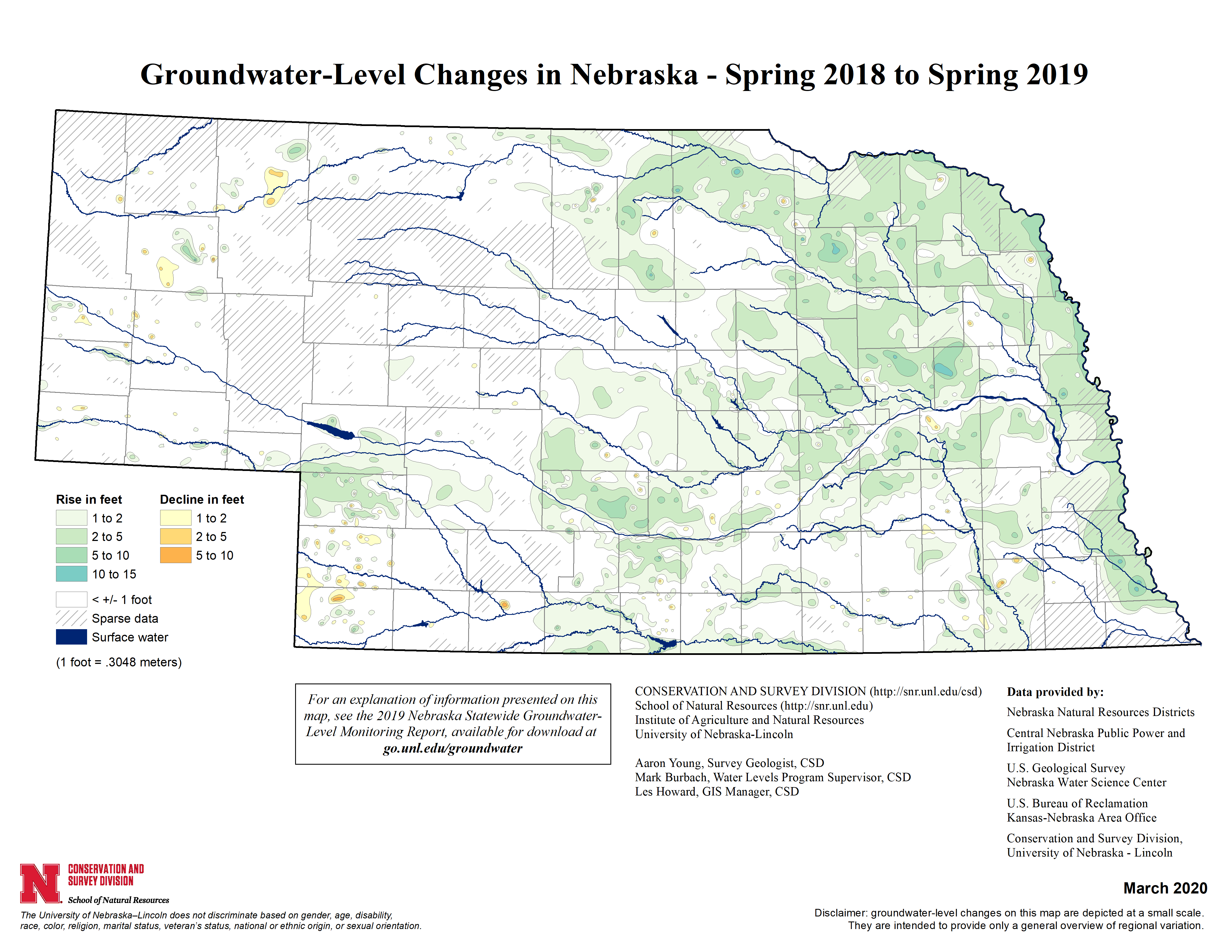

Young said that some pockets of the state, predominantly in southwestern Nebraska and the panhandle, saw minor groundwater level declines. But a map in the latest Groundwater-Level Monitoring Report that shows the changes from spring 2018 to spring 2019 in groundwater supply is mostly bathed in hues of green and blue, indicating a wealth of increases in groundwater supply across the rest of Nebraska. On average, wells measured in the spring of 2019 saw a 2.63-foot increase in groundwater levels statewide.

“That's a pretty significant rise,” Young said. “In many areas of the state, it doesn't completely offset, but it helps to offset, some of the declines we had from the drought in 2012 that are still lingering in many areas.”

Young said that there are some areas of the state that likely will not fully recover from the 2012 drought for an extended period of time, but one of the counties hit hardest by it had some of the biggest gains in groundwater last year.

Colfax County had about a 15-foot rise in groundwater levels this year, Young said, after about a 20- to 25-foot decline during the drought. The county, located about 75 miles west of Omaha, does not have a large irrigated-agricultural footprint compared to other rural Nebraska counties, so its residents most often experienced the lack of groundwater at personal levels, Young said. Due to the drought, many house wells there went dry.

Data used to compile the annual Groundwater-Level Monitoring Report are collected by 30 different state and local agencies, and Young leads a UNL effort to process the data, plot it and then hand draw maps that are published in the report. The goal, Young said, is to provide annual analysis about one of Nebraska’s most vital resources

“All this water is essential to our agricultural economy,” he said. “Without this, growing crops would be next to impossible in many parts of the state.”

The report, created at the Conservation and Survey Division at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Natural Resources, was written, researched and produced by Young, Mark Burbach, Leslie Howard, Susan Lackey and Matt Joeckel.

When the University of Nebraska reopens, the report will be available for $7 from the Nebraska Maps and More Store, 3310 Holdrege Street, Lincoln, NE 68583. Phone orders will be accepted at 402-472-3471. Order a printed copy or download a PDF at nebraskamaps.unl.edu.

Cory Matteson, SNR Communications