When rangeland managers see signs of drought, they may need to take action. During a significant flash drought that began in the early spring of 2016 and took hold in parts of the Northern Plains, 87% of managers who responded to a survey created by Tonya Haigh at the National Drought Mitigation Center said that they bought extra hay, grazed pastures earlier, or destocked herds.

But many of those surveyed did not begin taking action until the fall of 2016, even as the drought grew severe months earlier, and even as drought early warning and monitoring information sources such as the U.S. Drought Monitor, and products from the National Weather Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture showed signs of drought developing earlier in the year.

Haigh, a research specialist with NDMC, wrote that this offers an opportunity to understand proactive decision-making and improve outcomes for rangeland managers in a study, “Drought Early Warning and the Timing of Range Managers’ Drought Response,” that was recently published in “Advances in Meteorology.”

“It’s important to understand the decisions rangeland managers make during drought in order to provide drought early warning information that is relevant and actionable to them,” Haigh said.

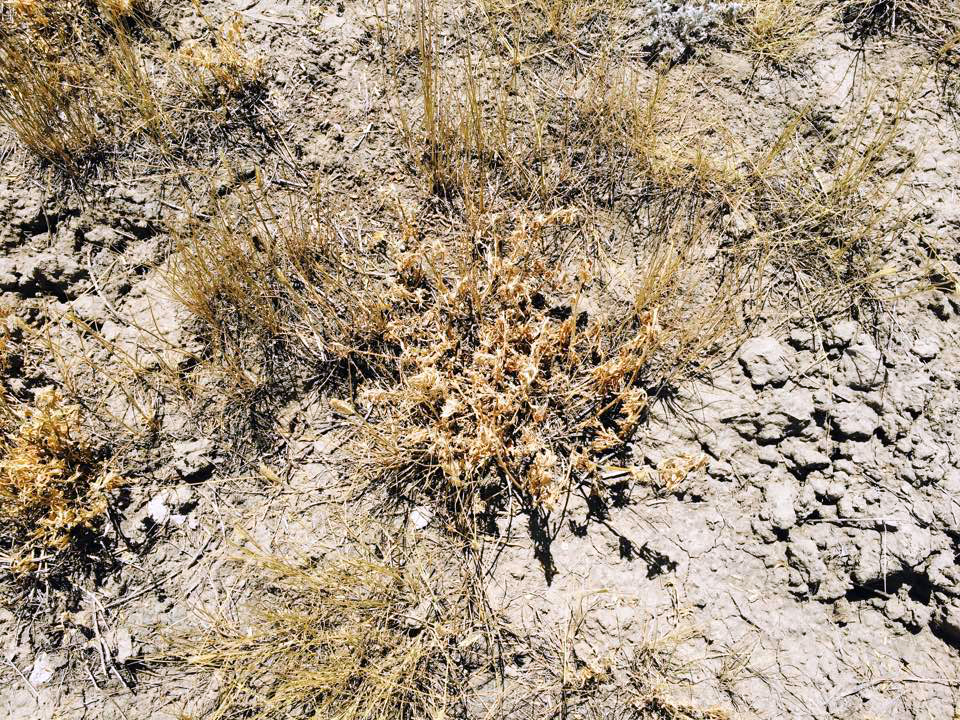

The study utilized information from a survey of agricultural producers in Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota and Montana who were affected by the flash drought that began to develop in late March of 2016. Participants were asked to indicate drought conditions (plant stress, decreased topsoil moisture, etc.) that occurred on their land, what steps they took in response to drought conditions and to estimate the degree to which the drought harmed productivity in terms of several categories, including pasture hay yield, range health and animal reproduction. They were also asked which sources they consulted for drought information, and how influential they considered those sources to be. Finally, they were asked if they would have acted earlier or differently had they received information that told them that the 2016 drought was starting and if they believed doing so would have lessened harm to their operation.

Though producers observed drought conditions such as decreased forage productivity over time as drought developed, the study found that producers did not immediately begin taking action. In addition, “external warnings did not influence the timing of their decisions, though on-farm monitoring and assessment of conditions did,” the study states.

Producers who destocked later in the year saw greater damages to pasture resources, and afterwards reflected that they could have had better outcomes had they responded differently.

“Though this case focused only on a one-year flash drought characterized by rapid drought intensification, waiting to destock pastures was associated with greater losses to range productivity and health and diversity,” the study states. “This study finds evidence of unrealized potential for drought early warning information to support proactive response and improved outcomes for rangeland management.”

Haigh added: “There is still room to improve proactive drought management on rangelands. Drought early warning information that supports managers’ own on-farm monitoring and lessens the uncertainties of decision-making may help close that gap.”

The study's coauthors include: Jason A. Otkin, University of Wisconsin-Madison Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies; Anthony Mucia, Centre National de Recherches Météorologiques/Météo-France; Michael Hayes, University of Nebraska-Lincoln School of Natural Resources; and Mark E. Burbach, UNL School of Natural Resources Conservation and Survey Division.

"Advances in Meteorology" is an open-access journal, and the entire study is available to view for free online at this link.

By Cory Matteson, NDMC Communications Specialist