By analyzing Google Earth images, a trio of University of Nebraska-Lincoln Conservation and Survey Division scientists discovered widespread, permanent ground ice, or permafrost, was common in northern Nebraska about 26,500 to 19,000 years ago when ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere were last at their greatest extent.

The discovery adds another dimension to the study of changing climates in Nebraska and the surrounding Great Plains, said Matt Joeckel, CSD director and co-author on the research published in the fall edition of Great Plains Research.

“We’ve known for more than a century and a half that the Midwest was partially covered by multiple advances of the Laurentide Ice Sheet (the large glacial sheet that moves down from Canada),” he said, “but we knew very little about conditions around the western margin of the glacial ice. Now we know a lot more, and we can build upon the results that were just published.”

To make the discovery, Joeckel; Paul Hanson, geologist; and Les Howard, geographic information systems and cartography manager, combed through Google Earth aerial images Earth covering an area of hundreds of square miles across Nebraska and South Dakota.

“We were stunned to find the evidence for ancient polygonal ground hiding in plain sight on the modern landscape — and in a few hundred places,” Joeckel said. “This is, by far, the best and most widespread evidence anyone has yet found for permafrost in Nebraska during the Last Glacial Maximum or, for that matter, at any other time during the Pleistocene ice ages.”

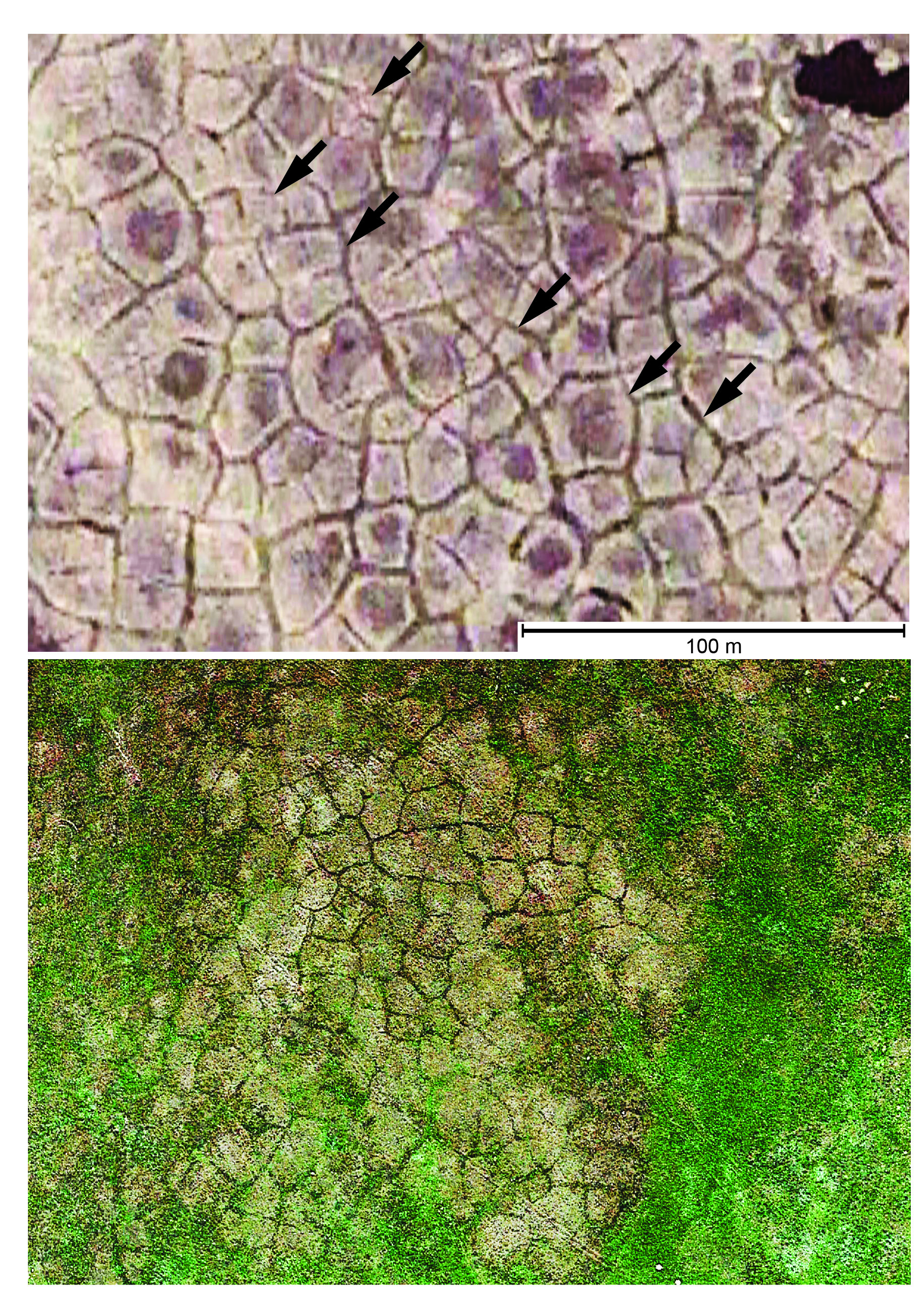

Polygonal ground describes the mosaic-like pattern of four- to seven-sided figures — tens of feet across — that can remain at the land surface after permafrost has melted away. It is caused by the contraction of soil and bedrock under very cold climatic conditions, a cold more intense and prolonged, by far, than the coldest winter modern Nebraskans have experienced. As the ground contracts, the cracks develop, only to be filled by a combination of ice and soil or sand, and when the ice melts away, the sediment in the cracks remains, preserving a record of former permafrost.

The researchers found visual evidence of these cracks in the Google Earth images, but only in those taken during certain months and years, mostly springtime, and under particular conditions of soil moisture, land use/cropping, and vegetation growth, the researchers said. The vast majority of aerial images did not capture the phenomenon, necessitating an exhaustive search through many years of images.

“The tedium of looking through the images was relieved by regular moments of excitement every time we located a patch of relict polygonal ground,” Joeckel said. “Although it is by no means a job for the easily discouraged, the search eventually got to be addictive, and in the end, it was definitely worth all of the effort.”

The researchers said the polygonal ground is always there at the land surface and extending just below it, and it may just be covered by vegetation or the difference in soil moisture is not great enough to highlight. The same ephemeral visibility of polygonal ground has been noted by others based elsewhere in North America and Europe.

The researchers plan to extend the research northward into South Dakota and also examine ancient periglacial features and climates across the Great Plains.

This discovery, and any from their future research plans, were possible because of geologic mapping funded by the U. S. Geological Survey’s STATEMAP Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program, in which the CSD has been involved for more than two decades.

Natural Resources