The new U.S. Climate Data Initiative, announced by the White House on March 19, includes a partnership involving the University of Nebraska-Lincoln with Google, the University of Idaho and the Desert Research Institute. In this partnership, Google will provide "vast cloud computing resources to spur creation of high-resolution drought and flood mapping, apps, and tools for climate risk resilience," according to a White House press release.

For Ayse Kilic, associate professor with UNL's Department of Civil Engineering and the School of Natural Resources, the partnership means a toolbox overflowing with resources, and she's eager to connect the public with the partnership's benefits.

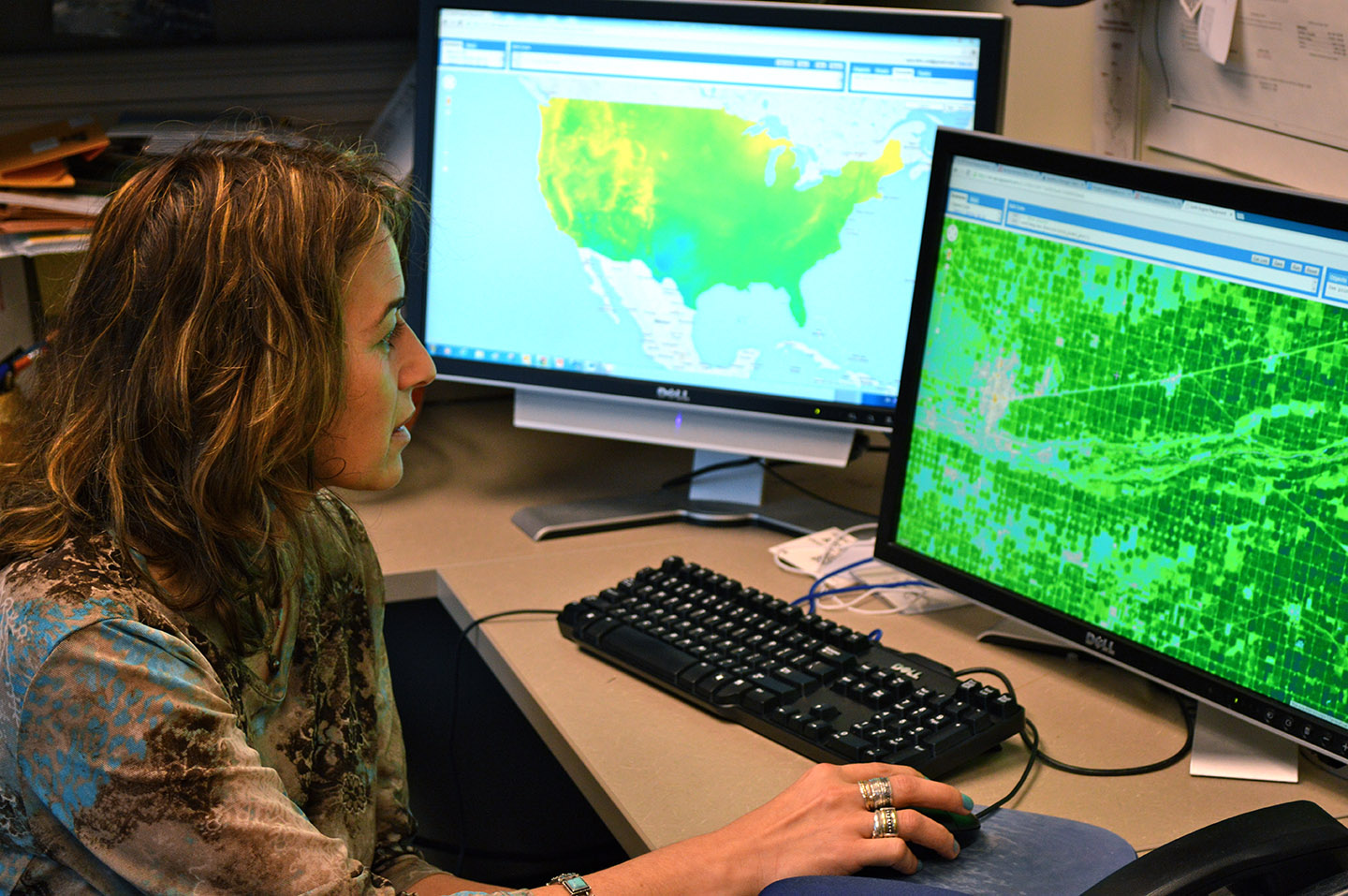

Kilic produces advanced high-resolution models for water use mapping and water resources management and is a leading contributor in the partnership, which aims to provide near real-time information on water consumption from vegetation across the entire planet at the field scale. The maps will support water conservation and be a key factor in developing drought monitoring inside Google Earth Engine for the entire continental United States. She will be building on her group's experiences from applications along the Platte River of Nebraska.

Google will provide one petabyte (1,000 terabytes) of cloud storage to house satellite observations, digital elevation data and climate and weather model datasets drawn from government open data and contributed by scientists. Fifty million hours of high performance cloud computing on the Google Earth Engine geospatial analysis platform will also be provided.

"It is exciting to work with the new technology of Google Earth Engine because it handles so much information about our planet," Kilic said. "Google Earth Engine is a water resources engineer's dream. The computer screen shows real-time water use information in just a few seconds, using the Google Computing Cloud. These processes once took hours on (even high-powered) computers."

Kilic's work focuses on evapotranspiration, or how water moves through the atmosphere as it evaporates from soil and water and transpires from plants. In 2013, she began a five-year term with an elite international team of 25 scientists supporting NASA's Landsat Data Continuity Mission Satellite or "Landsat 8."

She said Google has collected the entire modern Landsat archive's images of the planet, dating to 1984, which is "a tremendous and convenient resource for our application."

"Landsat satellite imagery provides us with 30 meter pixels that allow us to see inside individual agricultural fields," Kilic said. "The thermal band of Landsat is especially important. We will need even more Landsat satellites in the future for modern water management."

Graduate students Doruk Ozturk and Yao Li, remote sensing specialist Ian Ratcliffe and research assistant professor Baburao Kamble gain valuable experience on Kilic's team – developing code, designing new ways to detect and contend with clouds in images and using evapotranspiration mapping to fine-tune regional weather forecasting models.

Kilic said a new project with her UNL group will use Google resources to generate applications providing lawn water management information to homeowners and cities to support water conservation.

"This project will utilize high-resolution aerial photography available for much of the United States and couple it with continental weather data sets for the entire country plus seven-day weather forecasts to provide homeowners with up-to-date information on their watering needs," Kilic said. "(Our research) creates opportunities for educators to have extensive sets of spatial data in their classrooms to use for geographic information system instruction, remote sensing, water resources and hydrology – for college students all the way down to elementary school students."

— Carole Wilbeck, Engineering